Vicki Goldberg

The Persistence of History, The Insistence of Time

Lesbos, a Greek island embraced by the sea and decked out in a wide array of landscapes, also sports remnants of its long-ago and disparate histories. Dimitris Yeros has lived on Lesbos a great part of the past thirty-five years, mostly during summers, the rest of the time in Athens and sometimes New York. He is attuned to both the multi-layered history of the island and to the idea that time seems to have slowed down a bit there: he says that life goes on on Lesbos much as it has for years because the villagers like it that way, and the island is not deluged with tourists as some other Greek islands are.

A photographer and painter, Yeros was one of the first Greek artists to introduce video art, mail art, body art, and performance art. He has had 58 exhibitions in a number of countries. Apparently this has neither worn him out nor diminished his masterful ability to turn rocks and tattered reminders of the past, as well as male nudes posing in difficult ways in unexpected places, into works of art. Armed with that little magic machine, a camera, and that expandable human capacity we call imagination, he comes up with surprises, conundrums, and charms.

He is clearly in love with the island, both its present and its past, which are so visibly interlinked. Its antediluvian past makes a rather startling appearance: a jagged, bristling, vertical rock that twists as it ascends over placid, shallow water. Its irascible surface suggests at first glance that it might be a botched missile that strayed from some dark planet, but, well, it’s more likely to be a random piece of rock torn loose by one of the fierce volcanoes that gave birth to the island or disturbed it post partum during centuries long gone. At any rate, it serves a momentary purpose: a bird has found its pinnacle an accommodating perch.

Yeros finds another tall and somewhat similar rock formation on a beach, this one a mammoth triangle that he endows with a certain elegance by adding a diminutive horse and rider, the spaces between the horse’s delicate legs playing with the shape of the rock. Unsurprisingly, Lesbos is plentifully supplied with rocks. On a massive set of lighter-colored rocks in a dark sea, a naked man stands tall, as if to proclaim his dominance.

Yeros’s pictures of villages and villagers on Lesbos exhibit both sympathy and compositional clarity. A tiny church that has seen better days sits directly on the sea; a cloud hovers just above, cannily forming an extra protective roof. Elsewhere, a village climbs a hill above its reflection in a placid harbor, while on an adjacent hill five geese perform a military drill, marching behind one another in perfect order.

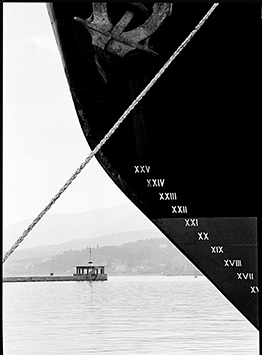

The sea provides food and work: in one photograph, fishermen work on their nets, which unfurl in gracious counterbalancing curves; below them lies a jumble of bubble-shaped floats piled up in slightly curving lines. And if such indications of the surrounding sea’s importance were not sufficient, a cleverly balanced image states it almost abstractly and quite succinctly: a diagonal slice of a freighter’s hull occupies nearly half the picture, a mooring line crosses it on an opposing diagonal, a horizontal pier in the near distance offers to meet that line just outside the frame.

One astonishing image suggests that the island’s verdant landscapes and rocky outcrops are not its entire story: this photograph centers on a long dead, Y-shaped tree in an endless, empty field of sand and a pervasive atmosphere of unidentifiable light — most likely from the sunset – that casts a dark shadow of the tree toward a low and apparently lightless moon in the distant sky.

In many reaches of Greece, history refuses to die quietly; instead it bequeaths its lingering remains to anyone who notices it doggedly keeping its place in the contemporary landscape. This is true on Lesbos as well -- and Yeros notices. Many of his Lesbos photographs play a complex game with time. Photography of course has a widespread and unearned reputation for stopping time, something not even a clever machine can do, for time does not stop. But Yeros and his camera pay their respects to several key moments in the island’s past and introduce them to a complex present.

The ancient Greeks have left behind column bases and pieces of a column itself. Rome bequeathed to the future a mighty aqueduct as well as a powerful statue of a lion seated upright, its front legs broken off and replaced by metal rods. But a little boy sits upon the lion’s pedestal, his little dangling legs a sly remark if not quite a replacement for the lion’s own. The medieval era entrusted to the future a stone bridge supported by a handsome arch. An ancient and frequently rebuilt fortress is attended by a flock of birds that has arranged itself to echo the outlines of the decrepit building and the land in front of it. The Turks left an old thermal bath (which today, Yeros writes with an exclamation mark, has been converted to a spa for the nouveaux riches), while “collapsing minarets” are most likely from a late nineteenth/early twentieth century mosque.

The past may lie in ruins, but it is always present.

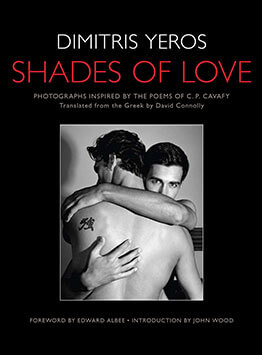

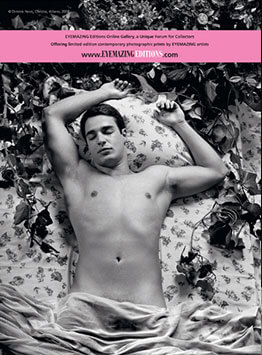

Yeros often places a young nude man upon the landscape and/or within or upon the stony witnesses of bygone eras. He is particularly famous for his photographs of the male nude, having published three books on that subject: For a Definition of the Nude, Theory of the Nude, and Shades of Love, which was on the shortlist for the ten top monographs honored by the American Library Association in 2011. John Wood, a poet and art and photography critic, wrote in his introduction to Shades of Love, “Yeros has created one of the most lyrical evocations of masculinity within the photographic arts.”

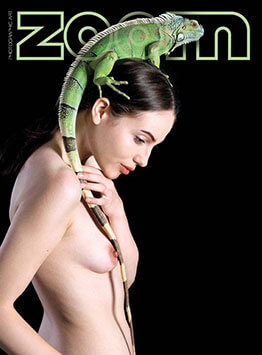

In fact, in For A Definition of the Nude he has indeed defined and obliquely explained nudity itself through pictures of male and female nudes holding animals. A man standing in profile holds a pig up to face him so the two of them can converse, another holds a bearded sheep against his pelvis, a woman embraces a peacock, another is embraced by a snake. The humans are naked but the animals are not undressed, for they were never dressed: they wear what they came into the world with. The pig wears only pig skin, which, as it happens, we value (the pig does too), the sheep has on an incipient blanket, the snake’s skin was probably designed by a fashionista, the peacock is garbed in glory.

Perhaps Eden looked like this before the fall, when the only two humans wore only their skin. Once chased out of paradise, they got dressed. “Naked” and “nude” are either the Lord’s decree, which created shame, or a concept defined by humans, some of whom at an early point decided they needed to be protected from the weather, and conceivably from sexual impulses. Neither “naked” nor “nude” is a word that applies to animals.

On Lesbos, Yeros’s images of young nude men play a sub rosa game with time. Nude men have had a long history without reference to the Eden story. For at least two centuries in pre-classical and classical Greece, the youthful nude male was a prominent figure. Kouroi (singular: kouros), sculptures of a generic, naked male athlete, stood for the high level of Greek civilization (and a professor I had in graduate school thought they also signified the moment of the greatest beauty and physical potential of the human being. Modern medicine comes pretty close to agreeing with that physical estimate.) The word ‘gymnasium’ comes from the Greek for ‘naked,’ and athletes in Panhellenic competitions might be naked, and Olympic athletes after a while shed all their clothes. Yeros’s photographs obliquely refer to this long-ago tradition in his country, placing his contemporary models metaphorically in two time frames at once.

Different times and cultures have regarded images of naked males differently. The nineteenth century thought them dangerous. The photographer Guglielmo Pluschow spent time in jail for corrupting minors. His cousin Wilhelm von Gloeden did better by arranging his pictures of young and largely undressed adolescents as classical groups and selling anything too explicit under the table. But women were to be protected at all costs: the painter Thomas Eakins was forced to resign from The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts because he removed a male model’s loincloth in a coed class.

Near the end of that century the physical fitness craze heralded a change of opinion, at least temporarily, though genitals stayed discreetly hidden. Opprobrium lingered. In the 1930s in America, George Hoyningen-Huene and George Platt Lynes, two fine photographers of the naked male, seldom saw those pictures presented in public; Lynes refused to exhibit his for fear they would ruin his career. For a long while after that it was illegal to send images of naked men through the U.S. mail.

Repeated attention to naked males has an air of homoeroticism, which is slightly ironic in this context, considering that Lesbos got its name from the great, and lesbian, female poet Sappho, who lived on the island. (A few scholars believe she was married and had a daughter, but much of the poetry by Sappho that still exists consists of love songs to girls and women.) At any rate, it’s worth noting that many, perhaps most, women respond esthetically and otherwise to a beautiful male body. And why not?

Yeros says that none of the young men he photographs are professional models, who work all too hard at looking professional. He looks upon his models as part of the landscape. Indeed there are images of men quietly declaring their importance, dominance, or unity with the landscape, like the one who stands tall on a massive rock formation in the sea, another partially visible from behind like an afterthought atop a rocky mountain, or two men who seem to belong in a cavern beside a plummeting water fall.

There are also men celebrated not for any apparent communication with the land but for their ability to perform feats of muscle and daring that twist their bodies into complicated postures. One such beautifully composed image, looking upward at an angle, finds the silhouette of a man climbing a geometric network of metal rods. Another admires a man who strains to twist an already twisted bicycle into unrecognizability.

Yeros initiated such images in 1989 with a photograph of himself standing in a complex pose at the distant end of the old bath, his shadow rendered crazed by his flash. More than two decades later he snapped a frightening, daring feat: a young man, seen suspended against the sky, is jumping from one mountain down to another – presumably, hopefully – there being no evidence of a safe place to land.

Time apparently has relaxed the fear or whatever it was of masculine nudity, at least in some places. Yeros not only ratifies the subject by association with antiquity but ties it to time by tying it to the island’s history. One youth lies on his back on what remains of a series of Greek column bases. Another stands on the arch of a Roman aqueduct. Yet another crouches before a medieval bridge; in a second image its arch frames a man, perhaps the same one, in the distance. Twice, male figures stand before minarets. More recent, but old enough to be decayed, is a ruined hotel where an elderly artist studies a young model, both of them nude. And a young gypsy fellow sits on the edge of a chair in an abandoned school that shows clear signs of neglect.

There are precedents for placing a nude of sorts before an ancient ruin: in the sixteenth century, an illustrated book on anatomy depicted a flayed figure before a ruin, doubtless a reminder that we too will decay one day. And Yeros’s young men in the prime of life before the crumbling remains of history seem to carry the same message, though the vibrant figures of the youths suggest that the short passage of individual humans in the face of time’s relentless advance can have its exuberant moments.

The moment a work of art leaves the artist’s hands he or she loses control of its meaning, which passes to observers. An onlooker could look at these photographs that so tellingly present the compression of centuries and could interpret them in a way or ways that says as much about the viewer as about the images.

Some might think that, as Macbeth had it, “all our yesterdays have lighted fools/The way to dusty death,” and we today will follow fools, emperors and empires down the same dusty path, though few of us will leave behind evidence strong enough to stand upon. Or, looking at such fine bodies, such physical strength, others might decide the message is that every generation is a fresh start and may realize its own greatness.

The repetition of several men with their backs to the remaining evidence of earlier achievements might also bring to mind that, as Santayana’s warning had it, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Or possibly such youthful figures accompanying the evidence of former greatness would remind us that “We are dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants” –a statement so meaningful it has been attributed to several prominent people.

Images as rich as these may well tease the mind with possibilities while pleasing the eye at the same time. T.S. Eliot once received a query from a student who had a theory about one of Eliot’s poems and wanted to know if that was indeed what the poet had had in mind. Eliot wrote back that it was not, but that it seemed to him a quite reasonable and defensible explanation.

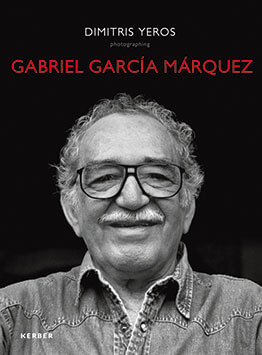

Yeros’s imagination, or inventiveness, also records nude bodies involved in pursuits intended mainly to delight the eye or puzzle the mind. There’s a fellow who holds up in each hand a wonderfully curving set of horns once worn by a kudu. Another young man standing before the sea holds up a fan-shaped branch composed of thin branches that seem to be swept by the wind into a delicate pattern. Yet another fellow, seen from shoulders to mid-thigh from the back, has crossed his arm behind his back. He holds a small bird in one hand; his arms cast dark shadows across his midriff and the bird casts inexplicable shadows over his buttocks. Then there’s a man seen from behind with his arms stretched wide for no apparent reason as he seems to contemplate or address a donkey in the middle distance. As the donkey has one ear standing almost straight up as if it were a horn, the man might almost as well be addressing a unicorn. Yeros was so friendly with Gabriel Garcia Marquez that he published a book of his portraits of that author: perhaps a little bit of magic realism rubbed off on the photographer.

The photographs explore human and nature’s beauty and intricate approaches to time: villagers preferring to live as they have for a long while, contemporary enough without being up to date. Persistent evidence of bygone centuries, the differently flavored eras of Greek history. Young bodies that time will not allow to stay as beautiful as they are. All of this seen with a keen eye, a knowledge of how convincing or beguiling a picture can be, and a camera that can set it all down in no time at all.

Vicki Goldberg, is an American photography critic, author, and photo historian. She has written books and articles on photography and its social history.

Goldberg has written for The New York Times and Vanity Fair. She has lectured in Belgium, England, France, China, Korea, Norway and Portugal as well as America. In 1997, she received the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award. In 1999, she received the Royal Photographic Society’s J Dudley Johnston Award.