Athena Schina: Man is the dream of a shadow

For me, Dimitris Yeros’s painting, and in particular the recent work he is currently exhibiting, calls to mind Pindar’s line: “Man is the dream of a shadow.” This verse, one of the fragments that survived because they were quoted so often by later authors in antiquity, serves to remind us not only of the fleeting shadow of a dream that is Man, but also of a safer option when we embark on a quest for the truth: just as we watch a solar eclipse through a tinted glass to avoid being blinded by the light, so can we search for truth as contrasted with darkness-that-is-not-truth.

We find this same peculiar concept of darkness as contrast (in a different form, of course) in a text Yeros wrote many years ago, in 1970, as a foreword to his show at the New Gallery (on Tsakalof Street). His short but revealing text addressed ‘suicides’ with an off-beat confession and what could only be described as an unorthodox testimonial for a young artist to choose to introduce himself to his audience with. By ‘suicides’, the young Yeros meant idealistic protests against a world which was up to its neck in conciliation. His foreword ended (with the “suicide of the train” or the “suicide of a mere bird”) with a list of causes which could drive a subject to destruction, meaning to suicide-homicide. In other words, Dimitris Yeros was already eliminating the distinction between the subject-observer and the surrounding objectivity of the world, expressing the things that constituted the psyche of the “primary roles depicted” through a reversal in the otherwise theatrical backdrop of his compositions.

Since then, Yeros has created a trademark figure/formula by removing and negating subjectivity. His human form (or thought form) stems from the urban environment of the metropolises that bear, raise and cast it/him out as a waste product of mass industrial production and of a suspicious exchange by which he/it is bought and sold, moulding the rules of an illicit game and of a tragedy played out on the shoals of existential needs and life’s founding conditions. In essence, the artist forms a persona which serves both as an alternative for his self and as an identification with each individual reader-viewer of the image, which he presents in a self-negating framework. His form-figure is running, dressed in his suit, trying to escape. He is usually running from right to left, which is to say contrary to the direction in which we read and write, because the imaginary routes the artist has him run subvert the customary flow of a conventional narrative, though without fragmenting its discourse.

I have made the above reference because Dimitris Yeros, apart from his underlying pain and self-sarcasm, maintains a poetic discourse in his surrealist-inspired works which contributes to forming a new ‘imaging act’ with successive, unrelenting, unexpected twists and turns, with touch-and-go balances and dead-ends, with visualized riddles and puzzles, but without empty cerebrality. His form-figure, both a vagrant and a fugitive, seeks out and at the same time runs away from the desires and passions that harry him like the Furies. He becomes a recluse under siege, entrapped in his freedoms and temporarily released from the traps that seek to tyrannize him. He runs—against the current, against the tide—between oases and threats, losses and expectations, utopias and chimaeras, places and times of memory and probability, the random and the written, the oneiric and the nightmarish, the repressed and the aspired to, between longing and frustration, traps and escape.

Yeros’s persona is both earthy and ethereal. It is subject neither to gravity nor to the laws of decay. It is persecuted and yet unimpugnable. It metamorphoses from perpetrator to victim, from narrator to narrated form-figure with the passions and never-ending adventures that make him exist as an adjectival attribute of his environment, but also as the agent of the action that represents him as moving, circulating, suffering (passively and reflexively), being pursued by his shadow and ‘winning’ or ‘losing’ the battles (or make-believe battles) that make him appear in or disappear from the firmament. In Yeros’s works, one might say that this firmament cosmogonically intercalates Plato’s the One and the Many by presenting, for instance, a flock of birds by means of a single idealized bird. The ‘firmament’ also contrasts and interweaves the distances and dimensions which the persona inhabits, forever linking, through contradictions and coexistences, the past and the everyday, memory and impression, verbal metaphor and visual allegories. It interweaves them as natural corollaries—undersea expanses with airspace, for example, birds with fish, natural formations with man-made forms, as the artist creates two-way channels of communication joining the (hypothetical) enclosed/internal rooms of introspection with the open-air/external spaces of the expression/manifestation.

This persona, based on the route it takes shadowing the reading gaze, also creates convergences with the waters and heavens, the sea voyages and winds, corridors, doors, openings and clearings which Yeros’s familiar life-giving creatures encounter and frequent—the forms that resemble raindrops, clouds and, at the same time, sperm cells as they conjoin the otherworldly and the erotic, death and life, transcendence and the risk of obscurity.

In his recent group of works, which are shaped by the above, Dimitris Yeros has cast out colour and opted for a Euclidean two-dimensional space. And even though he has used colour in his previous works, he knows this space and how to use it, selectively drawing on and creatively reworking elements from both the Byzantine folk and metaphysical traditions (the latter represented, in the main, by De Chirico). In this case, his allegorical subjects, as fleeting moments of the real and its tragedy but also of life’s laughter and tears, emerge as narratives and suspended acts in a theatre of shadows, enacting a new mute show each time with the laconic fragmentariness and allusive asceticism that inject life into these vertical and horizontal black-and-white elegies.

Through the shadows of things and the transitions from one dimension to another, which is to say from the nightmarish to the everyday, the viewer is presented with a bizarre shadow theatre behind whose stories lies the truth, to recall Pindar once again. In these works, the caravan of human life is observed by Edgar Allan Poe’s vigilant crow (magnified in bulk and length), as it crosses paths (on the Homeric Shores Gerasimos Steris once gave us) with the refugee drama. Elsewhere, two birds-a-flutter quarrelling in the face of the gulf separating all would-be communicators and the breakdown of all communication, illustrate the impasse.

Given that every image in Yeros’s work also functions as a visual pun, we note, for instance, the winged maker/artist turning into ‘us’ as he makes his escape (meaning he is transformed into every viewer or informal narrator), since we no longer seek through our plurality to experience everything mysterious and magic hinted at by this allegorical winged figure. Instead, in accordance with the mores of our contemporary era, we seek to capture the signifier, meaning the illusion of representation, in order to keep it as evidence and as a situational condition, taking the maker/artist hostage and turning him into a spectacle through our camera lens. In other words, we attempt to record and ultimately save or archive the latent reality by constructing what might be supposed to be the ‘land registry’ of our memory, which we have been perversely conditioned to perceive of in institutional terms, too, and to acknowledge as evidence and concomitant to our presence, which is confirmed through mechanical or other types of intervention. The various aspects and levels of reality are nor recorded with self-awareness and free will, but through intermediations and, ultimately, restrictions on the self. At this point, I would also like to refer to Yeros’s work with the Chinese tourist and VIPs who came to Greece as exotic observers to supposedly record the misery of the refugees and, of course, to monetize it on the altar of their fame with the fuel of extra publicity, since the treachery of the powers-that-be and their media have succeeded in transforming human misery into hypocrisy, a fashion. Moreover, Turkish Friend, with its refugees progressing towards a salvation devoid of hope, a utopia that does not exist, makes it quite clear that our so-called ‘friend and neighbour’, that human trafficking exploiter and tyrant, now poses a constant threat that leaves no room for complacency.

But then there is the Jumper (Altes) in the work of the same name, who brings hope—albeit imaginary hope—that the obstacles can somehow be surpassed. Altes expresses this hope as a craving more cerebral than physical, as a hazy desire rather than a possibility, doing so in order to banish the fear and darkness he bears within as he flies over the fateful void.

Typical of this group of works is the painting of the man turning into a tree for the birds of the air, his arms becoming branches and perches for nature’s creations (and denoting transcendence of another type). I would add that the human figure in this work also initiates a dialogue with Da Vinci’s Homo Universalis, a work that would indelibly mark the spirit of the Renaissance. In it, the human figure is facing the viewer; transformed into the centre of the world, everything revolves around him and is obliged to serve him. In contrast, Yeros’s human figure (which runs counter to the Renaissance, and primarily to its centrifugal tendencies) is depicted with its back to the viewer, its centripetal body (its outstretched arms as branches) becoming a receptor for nature and part of its cycle of cause and effect.

In addition to the above, I would like to note the composition here with its pyramid of deer depicted as a bizarre abacus. Every precariously balanced deer hosts within itself Plato’s Many—other beasts, species and variations on them in which everything acquires an identity in accordance with its position and quality, its impact and mode of presentation, its associations and the affinities they denote.

However, in terms of their condemnation and sarcastic mauling of social hypocrisy and the corrosive race to the bottom initiated by the powers-that-be, the works culminate in the artist’s ‘protest works’ (to recall the ‘suicidal’ way in which Dimitris Yeros first manifested his refusal to compromise). These works include his monkeys, which caricature the powerful, along with other works in which Yeros—troubled and distraught at what he is observing, but full of fury and the desire to show things exactly as they are—initiates the viewer without prevarications into the system of refugee ‘transport’ in which a lifejacket can also be read as a funerary wreath for the escapees and wanderers who succumb to the perils of their trip and pay with their lives for the dream of freedom.

In this group of works, the artist shadow-boxes with the dilemmas life presents. He is more austere and vitriolic, more enigmatically succinct and allusively compact. But, thanks to a stealthy but controlled sentimentalism, his narrative never loses sight of its goals as its meanings—indeed, it is enhanced on multiple levels. Self-critical, willing to rethink and pour scorn on his work, to call conventions into question, stoic and erotic, with equal doses of humour and pain that leave him (and us) unsure whether to laugh or cry, Dimitris Yeros inducts his viewers into a different climate each time, which makes them decode more directly the notation of the subjects he reads visually and feels almost musically. Through the aroma of and longing for a paradise lost, his subjects simultaneously represent and reference broader areas of the mind and the imagination. And we can be quite certain that these bright, shimmering expanses convey the gaze to their white and unconfessed truths which, unrecorded, we somehow sense to exist far beyond their black and white visual display.

Athena Schina is an art critic and historian. She has taught Art History at Athens University. She curates and serves as artistic director for all exhibitions staged at both the Petros & Marika Kydonieos Foundation on Andros and the Rhodes municipal Museum of Neohellenic Art.

Αθηνά Σχινά: Σκιάς όναρ γαρ άνθρωπος

Η ζωγραφική του Δημήτρη Γέρου, κυρίως η πρόσφατή του ενότητα που εκθεσιακά παρουσιάζει, με μεταφέρει συνειρμικά στον στίχο του Πινδάρου «σκιάς όναρ γαρ άνθρωπος». Ο στίχος αυτός που ανήκει στα αποσπάσματά του, - τα οποία μέσα από τις συχνές αναφορές τους διέδωσαν επιγενέστεροι του Πινδάρου συγγραφείς – έμεινε, όχι μόνο για να θυμίζει την εφήμερη και φευγαλέα σκιά ονείρου που είναι ο άνθρωπος, αλλά έναν ασφαλέστερο τρόπο που μπορούμε να επιλέξουμε, για να αρχίσουμε να αναζητούμε την αλήθεια, (όπως κοιτάζουμε την έκλειψη του ηλίου, μέσα από το καπνισμένο γυαλί, για να μην τυφλωθούμε από το φως), δηλαδή μέσα από το αντιθετικό σκοτάδι.

Αυτό το ιδιόμορφο κι «αντιθετικό» σκοτάδι, το συναντά κανείς με διαφορετικό φυσικά τρόπο, σε ένα αρκετά παλιό κείμενο (1970) του Δημήτρη Γέρου, με το οποίο προλόγιζε ο ίδιος την έκθεσή του στην «Νέα Γκαλερί» (της οδού Τσακάλωφ). Το σύντομο, όσο και αποκαλυπτικό εκείνο κείμενο που ο ίδιος υπέγραφε, αφορούσε τις «αυτοκτονίες», με μια παράδοξη ομολογία και με ένα ανορθόδοξο θα λέγαμε πιστοποιητικό, για την αρχή της συστατικής παρουσίασης ενός νέου καλλιτέχνη προς το κοινό του. Τις «αυτοκτονίες», τις εννοούσε τότε ο νεαρός ζωγράφος ως ιδεαλιστικές διαμαρτυρίες απέναντι σε έναν κόσμο πνιγμένο στην συνδιαλλαγή, καταλήγοντας (με την «αυτοκτονία του τραίνου» ή την «αυτοκτονία ενός ελάχιστου πτηνού»), σε μια σειρά αιτίων που εξωθούσαν το υποκείμενο στην καταστροφή, δηλαδή στην «αυτοκτονία-δολοφονία». Με άλλα λόγια, ο Δημήτρης Γέρος καθαιρούσε, από εκείνη ήδη την εποχή, την διάκριση ανάμεσα στο «υποκείμενο-παρατηρητή» και στον περιβάλλοντα αντικειμενικό του κόσμο, εκφράζοντας τα πράγματα που συνιστούσαν τον ψυχισμό των «εικονιζομένων πρωτοβάθμιων ρόλων», μέσα από μια αντιστροφή, στην – κατά τα άλλα - θεατρικού τύπου αυλαία των συνθέσεών του.

Ο Δημήτρης Γέρος έχει έκτοτε δημιουργήσει τον δικό του επινοημένο ανθρωπότυπο, προερχόμενο μέσα από την αφαίρεση και την κατάργηση του υποκειμενισμού. Ο δικός του ανθρωπότυπος (ή ένα είδος σκεπτομορφής) πηγάζει ως απορροή από το αστικό περιβάλλον των μεγαλουπόλεων, που τον γεννά, τον εκτρέφει και τον αποδιώχνει, ως απόβλητο παράγωγο της μαζικής βιομηχανικής παραγωγής και μιας ύποπτης συναλλαγής που τον πωλεί και τον αγοράζει, διαμορφώνοντας τους κανόνες ενός αθέμιτου παιχνιδιού και μιας τραγωδίας που παίζεται στα ύφαλα των υπαρξιακών αναγκών και των καταστατικών συνθηκών της ζωής. Κατ’ ουσίαν, ο ζωγράφος διαμορφώνει μια persona, που αφενός λειτουργεί ως ετεροπροσωπία του εαυτού του, αφετέρου ταυτίζεται με τον εκάστοτε αναγνώστη-θεατή της εικόνας, που την παρουσιάζει μέσα από αυτοαναιρούμενα πλαισιωτικά στοιχεία. Ο ανθρωπότυπός του, ντυμένος με το κοστούμι του, τρέχει προσπαθώντας να αποδράσει. Συνήθως τρέχει από τα δεξιά προς τα αριστερά, αντίθετα από τον τρόπο με τον οποίο γράφουμε και διαβάζουμε (από τα αριστερά προς τα δεξιά), γιατί μέσα από τις φαντασιακές πορείες που ο ζωγράφος τον κάνει να διανύει, ανατρέπει την συνήθη ροή της συμβατικής «αφήγησης», χωρίς ωστόσο να κατακερματίζει τον λόγο της.

Αν έκανα την παραπάνω αναφορά, είναι γιατί ο Δημήτρης Γέρος, πέρα από την υφέρπουσα οδύνη και τον αυτοσαρκασμό, διατηρεί έναν λόγο ποιητικό, στα υπερρεαλιστικής έμπνευσης έργα του, προκειμένου να προβεί στην διαμόρφωση μιας νέας «εικονοποιητικής πράξης», με συνεχείς, αλληλοδιάδοχες κι απροσδόκητες ανατροπές, με οριακές ισορροπίες κι αδιέξοδα, με οπτικοποιημένους γρίφους κι αινίγματα, αλλά χωρίς εγκεφαλισμούς. Ο ανθρωπότυπός του, πλάνητας και δραπέτης, επιδιώκει και ταυτοχρόνως αποφεύγει τις επιθυμίες και τους πόθους του, που τον καταδιώκουν σαν τις Ερινύες. Γίνεται πολιορκημένος αναχωρητής, φυλακισμένος μέσα από τις ελευθερίες του και λυτρωμένος προς στιγμή μέσα από τις παγίδες που καραδοκούν να τον δυναστεύσουν. Τρέχει –αντίθετα από το ρεύμα – ανάμεσα σε οάσεις κι απειλές, σε απώλειες κι αναμονές, σε ουτοπίες και χίμαιρες, σε τόπους και χρόνους της ανάμνησης και της πιθανότητας, του τυχαίου και του μοιραίου, του ονειρικού και του εφιαλτικού, του απωθημένου και της προσδοκίας, της λαχτάρας και της ματαίωσης, των παγίδων και της διαφυγής.

Η persona του Δημ. Γέρου είναι γήινη κι αέρινη. Δεν υπακούει στους νόμους της βαρύτητας, ούτε της φθοράς. Είναι διωκόμενη και ταυτοχρόνως ακαταδίωκτη. Μεταμορφώνεται από θύτης σε θύμα, από αφηγητής σε αφηγούμενος (ανθρωπότυπος) με τα πάθη και τις ατέλειωτές του «περιπέτειες», που τον κάνουν να υπάρχει ως επιθετικός προσδιορισμός του περιβάλλοντός του, αλλά και ως ρηματική ενέργεια της «δράσης» που τον παριστάνει να κινείται, να κυκλοφορεί, να πάσχει (στην μέση και παθητική του φωνή), να κυνηγιέται επίσης από την σκιά του και να «κερδίζει» ή να «χάνει» τις μάχες (ή τις σκιαμαχίες) που τον κάνουν να εμφανίζεται κι άλλοτε να εξαφανίζεται από το «στερέωμα». Αυτό το «στερέωμα», στα έργα του Δημήτρη Γέρου, παρενθέτει κοσμογονικά θα λέγαμε, το «έν» και τα «πολλά» του Πλάτωνα, καθώς παρουσιάζεται π.χ. μέσα από μια μορφή ιδεατού πτηνού, ένα σμήνος πουλιών και ούτω καθεξής. Το «στερέωμα» επίσης αυτό αντιπαραβάλλει και διαπλέκει τις αποστάσεις και τα μεγέθη, (μέσα στα οποία ζει η persona), ενώνοντας πάντα με αντιδιαστολές και συνυπάρξεις, το παρελθόν με την καθημερινότητα, την μνήμη με την εντύπωση, την μεταφορικότητα του λόγου με τις αλληγορίες της εικόνας. Τις διαπλέκει, σαν ένα φυσικό επακόλουθο, όπως π.χ. τις υποθαλάσσιες εκτάσεις με τον εναέριο χώρο, τα πτηνά με τους ιχθύες, την «πλάση» της φύσης με την «διάπλαση» των μορφών, καθώς ο καλλιτέχνης δημιουργεί παράλληλες επικοινωνιακές συναρτήσεις των (υποθετικών) εσωτερικών και «κλειστών» δωματίων της «ενδοσκόπησης» με τους εξωτερικούς και υπαίθριους χώρους της εκφραστικής «εκδήλωσης».

Η persona αυτή, με βάση την περιδιάβαση την σχετική με την «ανάγνωση» του βλέμματος, δημιουργεί επίσης συγκλίσεις με νερά και ουρανούς, με ταξίδια θαλασσινά κι ανέμους, με διαδρόμους και θύρες ή ανοίγματα και ξέφωτα, όπου χαρακτηριστική είναι η συχνή και πυκνή κυκλοφορία των χαρακτηριστικών και ζωογόνων όντων του Δημήτρη Γέρου, εκείνων που θυμίζουν σταγόνες της βροχής, σύννεφα και ταυτοχρόνως σπερματοζωάρια, καθώς συνενώνουν το απόκοσμο με το ερωτικό στοιχείο, τον θάνατο με την ζωή και τον κίνδυνο της αφάνειας με την υπέρβαση.

Στην πρόσφατη ενότητα των έργων, που είναι διαμορφωμένα στην βάση των παραπάνω χαρακτηριστικών του γνωρισμάτων, ο Δημήτρης Γέρος εξοβελίζει το χρώμα, επιλέγοντας τον Ευκλείδειο δισδιάστατο χώρο. Ούτως ή άλλως, τον γνωρίζει αυτόν τον χώρο και τον χρησιμοποιεί, αντλώντας επιλεκτικά και μεταπλάθοντας δημιουργικά, στοιχεία από την βυζαντινολαϊκή, αλλά και από την μεταφυσική παράδοση, κυρίως του De Chirico, έστω κι αν (στα προηγούμενά του έργα) χρησιμοποιεί χρώματα. Στην προκειμένη περίπτωση, τα αλληγορικά του θέματα, σαν φευγαλέες στιγμές της πραγματικότητας και της τραγωδίας της, αλλά και του κλαυσίγελου της ζωής, αναφύονται ως «αφηγήσεις» και μετέωρες πράξεις σε ένα θέατρο σκιών, διαγράφοντας μια παντομίμα κάθε φορά, μέσα από την λακωνική αποσπασματικότητα και την υπαινικτική ασκητικότητά τους, που υποδόρια ζωντανεύει τις κατακόρυφες κι οριζόντιες αυτές ασπρόμαυρες ελεγείες.

Ο θεατής, μέσα από τις σκιές των πραγμάτων και των «περασμάτων» από την μία διάσταση στην άλλη, από τον εφιάλτη δηλαδή στην καθημερινότητα, παρακολουθεί ένα παράδοξο «θέατρο σκιών», πίσω από τις «ιστορίες» του οποίου, βρίσκεται η αλήθεια, για να θυμηθεί ξανά κανείς τον Πίνδαρο. Στα έργα αυτά, το ανθρώπινο καραβάνι, το παρακολουθεί (μεγιστοποιημένο σε όγκο και μέγεθος) το άγρυπνο κοράκι, που κράζει μέσα από τους στίχους του Edgar Allen Poe, συναντώντας, (στα αλλοτινά θαρρείς «Ομηρικά Ακρογιάλια» του Γεράσιμου Στέρη), το δράμα της προσφυγιάς. Αλλού, δυο αλαφιασμένα πουλιά, που φιλονικούν, μπροστά από το ρήγμα και ταυτοχρόνως την ρήξη κάθε συνεννόησης, καθιστούν εμφανή τα αδιέξοδα.

Αφ’ης στιγμής η κάθε εικόνα λειτουργεί παράλληλα και ως λογοπαίγνιο, στο έργο του Δημήτρη Γέρου, παρατηρούμε πως π.χ. ο «ποιητής» γυμνός, με τα φτερά στους ώμους, καθώς δραπετεύει, μετατρέπεται την ίδια στιγμή στο «εμείς» (δηλαδή στον κάθε θεατή ή άτυπο αφηγητή), καθώς μέσα από τον πληθυντικό μας αριθμό, προσπαθούμε όχι πλέον να βιώσουμε ως λειτουργία ό,τι μυστήριο και μαγικό υποδεικνύει η αλληγορικά φτερωτή αυτή φιγούρα. Επιδιώκουμε, σύμφωνα με τα ήθη της σύγχρονής μας εποχής, να «αποτυπώσουμε» για να «συγκρατήσουμε» ως αποδεικτικό στοιχείο και καταστατική συνθήκη, το «σημαίνον», δηλαδή την φενάκη της παραστατικότητας, δεσμεύοντας κατ’ αυτό τον τρόπο τον ίδιο τον «ποιητή» ως όμηρο και θέαμα, μέσα από την φωτογραφική ή την κινηματογραφική μας άλλοτε μηχανή.

Προσπαθούμε με άλλα λόγια, να αποτυπώσουμε κι εντέλει να αποθηκεύσουμε ή να «αρχειοθετήσουμε» την πραγματικότητα που διαρκώς λανθάνει, χτίζοντας υποτίθεται το «κτηματολόγιο» της μνήμης μας, καθώς έχουμε πλέον διαστροφικά «εκπαιδευτεί» να την προσλαμβάνουμε και θεσμικά να την «αναγνωρίζουμε» ως αποδεικτικό στοιχείο και σύστοιχο αντικείμενο της παρουσίας μας, που επιβεβαιώνεται μέσα από μηχανικές ή άλλου τύπου παρεμβάσεις. Οι ποικίλες όψεις και τα διαφορετικά επίπεδα της πραγματικότητας, δεν «καταγράφονται» με αμεσότητα συναίσθησης κι ελευθερία βούλησης , αλλά με διαμεσολαβήσεις και περιστολές εντέλει του «εαυτού». Στο σημείο αυτό, θα ήθελα επίσης να παραπέμψω στο έργο του Δημήτρη Γέρου, με τον «κινέζο» τουρίστα αλλά και σε επώνυμους «επισκέπτες» της χώρας μας, που ήρθαν ως «εξωτικοί» παρατηρητές για να αποτυπώσουν υποτίθεται την δυστυχία των προσφύγων και φυσικά να την εξαργυρώσουν στο βωμό της φήμης τους και της περαιτέρω διαφήμισης, αφ’ης στιγμής η δολιότητα της εξουσίας και των μέσων προβολής, κατάφερε να μετατρέψει την ανθρώπινη δυστυχία, σε υποκρισία και ζήτημα «μόδας». Στο έργο επίσης, ο «Τούρκος φίλος», με την ανθρώπινη πορεία των μεταναστών προς την απέλπιδα «σωτηρία» ή την ουτοπία, καθίσταται έντονα εμφανής η περίπτωση του ψευδεπίγραφου «γείτονα-φίλου», του «διακινητή-εκμεταλλευτή» και τυράννου που ασκεί καθημερινή πλέον απειλή, με απουσία κάθε μορφής εφησυχασμού.

Από την άλλη πλευρά, ο «Άλτης» στο ομώνυμο έργο του Δημήτρη Γέρου, δίνει μια ελπίδα, έστω και σε φαντασιακό επίπεδο, για την υπέρβαση των εμποδίων. Την ελπίδα αυτή, ο «Άλτης» την εκφράζει ως ψυχική περισσότερο λαχτάρα και πόθο μακρινό, παρά ως πιθανότητα, προκειμένου να εξοστρακιστεί ο φόβος και το σκοτάδι, που φέρει εντός του, καθώς ίπταται πάνω από το κενό ή το μοιραίο «χάσμα».

Ένα από τα χαρακτηριστικά έργα, στην αναφερόμενη αυτή ενότητα, είναι και το έργο του ανθρώπου που μεταμορφώνεται σε δέντρο για τα πετεινά του ουρανού, (δηλώνοντας έναν άλλο τύπο υπέρβασης), όπου τα χέρια του γίνονται κλαδιά και επιφάνειες στήριξης, για τα όντα της φύσης. Θα συμπλήρωνα, πως η ανθρώπινη αυτή φιγούρα, εκτός των άλλων, ανοίγει στο συγκεκριμένο έργο κι έναν παράλληλο διάλογο με τον Homo Universalis του Da Vinci. Πρόκειται για το έργο που σηματοδοτεί το γενικότερο πνεύμα της Αναγέννησης. Εκεί, ο «ανθρωπότυπος», με μέτωπο προς τον θεατή, μετατρέπεται στο κέντρο του κόσμου, όπου κάθε τι οφείλει να τον υπηρετεί, περιστρεφόμενο γύρω του. Ο «ανθρωπότυπος» του Δημήτρη Γέρου, (που αντιστρατεύεται την Αναγέννηση, κυρίως τις φυγόκεντρες τάσεις της), παριστάνεται με αντιθετικότητα, δηλαδή με τα νώτα του στραμμένα προς τον θεατή, καθώς το «κεντρομόλο» σώμα του, (με τα απλωμένα του χέρια ως κλαδιά), γίνεται «υποδοχέας» πλέον της φύσης και μέρος των νομοτελειών της.

Εκτός των ανωτέρω, θα ήθελα επιπλέον να επισημάνω, την εικαστική εκείνη σύνθεση του καλλιτέχνη, με την «πυραμίδα» των ελαφιών, όπου παριστάνεται ως ένα παράδοξο αριθμητήριο. Καθένα ελάφι, ισορροπώντας οριακά, φιλοξενεί εντός του τα «πολλά» άλλα ζώα (και είδη) του Πλάτωνα, καθώς και τις παραλλαγές τους, όπου όλα αποκτούν «ταυτότητα», ανάλογα με την θέση και την ποιότητα, την επενέργεια και τον τρόπο παρουσίασης, τους συσχετισμούς και τις συνάφειες που υποδηλώνουν.

Αποκορύφωμα ωστόσο, ως προς το καταγγελτικό ύφος και τον απροκάλυπτο σαρκασμό για την κοινωνική υποκρισία, καθώς και για τον κατολισθητικό ή αποσαθρωτικό ρόλο που παίζει η κάθε μορφής εξουσία, είναι τα «έργα-διαμαρτυρίες» του καλλιτέχνη (για να θυμηθούμε τον «αυτοκτονικό» τρόπο με τον οποίο ξεκίνησε να εκδηλώνει την άρνηση συμβιβασμού του ο Δημήτρης Γέρος). Στα έργα αυτά περιλαμβάνονται και οι «μαϊμούδες» του, που γελοιογραφούν πρόσωπα της εξουσίας. Σε άλλα έργα, της ίδιας αυτής ομάδας, με πόνο ψυχής, εσωτερικό σπαραγμό, αλλά με καυστικότητα και χωρίς περιστροφές, ο Δημ. Γέρος, παρακολουθεί και μυεί τον θεατή, με απουσία υπεκφυγών, προς την θαλάσσια «μεταγωγή» των μεταναστών, όπου το σωτήριο σωσίβιο εκλαμβάνεται και ως μεταθανάτιο στεφάνι για τους δραπέτες και πλάνητες της ζωής, όταν η απειλή κι ο κίνδυνος γίνονται μια μοιραία κατάληξη κι ένα σκληρό τίμημα για την πολυπόθητη ελευθερία.

Σε αυτή του την ομάδα έργων, ο ζωγράφος σκιαμαχεί με διλήμματα της ζωής. Είναι περισσότερο λιτός και δραματικά καυστικός, πιο αινιγματικά περιεκτικός και υπαινικτικά πυκνός. Η αφηγηματικότητα της πλοκής δεν χάνει, λόγω ενός υφέρποντος, αλλά ελεγχόμενου συναισθηματισμού, τους στόχους της, καθώς ενδυναμώνει τα ποικίλα επίπεδα των σημασιών της. Ο Δημήτρης Γέρος με κριτική και αυτοσαρκαστική, με αναθεωρητική και στοχαστική διάθεση, με στωικότητα και κλαυσίγελο, με ερωτισμό κι αποκαθήλωση των συμβάσεων, χωρίς να λείπει το χιούμορ κι ο πόνος, υποβάλλει στον θεατή ένα ιδιαίτερο κάθε φορά κλίμα, το οποίο τον κάνει να αποκωδικοποιεί αμεσότερα την παρασημαντική των θεμάτων που οπτικά εκείνος διαβάζει και μουσικά σχεδόν αισθάνεται. Τα συγκεκριμένα θέματα, μέσα από το άρωμα και την νοσταλγία του «χαμένου παραδείσου», παριστάνουν, αλλά και την ίδια στιγμή παραπέμπουν σε ευρύτερες εκτάσεις του νου και της φαντασίας. Και είναι σίγουρο, πως αυτές οι ανέσπερες και φωταυγείς εκτάσεις, μεταφέρουν το βλέμμα στις λευκές και ανομολόγητές τους αλήθειες, τις ακατάγραφες, που τις διαισθανόμαστε να υπάρχουν, πέρα και πολύ μακρύτερα από την ασπρόμαυρη, εικαστική τους οθόνη.

Η Αθηνά Σχινά είναι κριτικός και ιστορικός της Τέχνης. Έχει διδάξει Ιστορίας της Τέχνης στο Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών και είναι καλλιτεχνική διευθύντρια και επιμελήτρια όλων των εκθέσεων του Ιδρύματος Π. & Μ. Κυδωνιέως της Άνδρου και του Μουσείου Νεοελληνικής Τέχνης του Δήμου Ρόδου .

As a contemporary Greek artist, Dimitris Yeros stands in close proximity to Hellenic antiquity and its afterlives. Yeros uses this proximity, however, as the point of departure for an ironic distancing. Several of Yeros's most arresting images feature models in conspicuously classical postures, at once citing and revivifying antique sculpture. These works cast the male viewer as a modern-day Pygmalion, apostrophizing that which Winckelmann felt upon seeing a Roman youth of his day — as a “most antique living beauty.” Yeros’s photographs in the present show, by contrast, seek to disrupt, or at least to question, the smooth elision between "antique" and "living" as embodied in the male form. Yeros invokes this disruption, here and in other related works, through various props: a plant set in a contemporary vase, a peacock or a duck, a prominent tattoo, a puckering pig. Butterflies, for example, recalls Man Ray's Violon d'Ingres, in which the artist adds two f-volutes to a female nude's back, spoofing the languid classicism of Ingres's Odalisque, as well as performing his own erotic transformation of the body. Yeros's props similarly unravel the seam between antiquity and the present, and not without a dose of wry humor in turn. Do Yeros's images represent meditations on the irreconcilableness of these worlds? The photographs seem less ponderous than that. They are playful and punning, even in their meticulous framing and spare decor, their poker-faced aplomb. These bodies are comfortable in their contemporaneity. But that their attendant feathered and furry malapropisms do not diminish their engagement with classical art is testament to Yeros's deftness as a photographer.

ARA H. MERJIAN

From the exhibition “Classicism Subverted” Paris April-May 2005

Ως σύγχρονος Έλληνας καλλιτέχνης, ο Δημήτρης Γέρος βρίσκεται πολύ κοντά στην ελληνική αρχαιότητα και τις μετεξελίξεις της. Ο Γέρος, ωστόσο, χρησιμοποιεί αυτή την εγγύτητα σαν αφετηρία για μια ειρωνική αποστασιοποίηση. Μερικές από τις πιο συναρπαστικές εικόνες του Γέρου παρουσιάζουν μοντέλα σε στάσεις εμφανώς αρχαιοπρεπείς, που αποτελούν αναφορά σε αγάλματα της αρχαιότητας και ταυτόχρονα τα αναβιώνουν. Αυτά τα έργα τοποθετούν τον θεατή στο ρόλο ενός σύγχρονου Πυγμαλίωνα, που επαναλαμβάνει αυτό που ένιωσε ο Winckelmann όταν είδε έναν νεαρό Ρωμαίο της εποχής του «σαν την πιο αρχαία ζώσα ομορφιά». Σε αντίθεση, οι φωτογραφίες του Γέρου σ’ αυτή την έκθεση επιδιώκουν να διασπάσουν ή τουλάχιστον να θέσουν σε αμφισβήτηση την ομαλή έκθλιψη ανάμεσα στο «αρχαίο» και το «ζωντανό» όπως ενσαρκώνεται στην ανδρική μορφή. Ο Γέρος παραπέμπει σ’ αυτή τη διάσπαση, εδώ και σε άλλα συναφή έργα του, μέσα από τον σκηνικό του διάκοσμο: ένα φυτό μέσα σ’ ένα σύγχρονο βάζο, ένα παγόνι ή μια πάπια, ένα ευδιάκριτο τατουάζ, ένα γουρουνάκι με σουφρωμένη μουσούδα. Οι Πεταλούδες, για παράδειγμα, θυμίζουν το Βιολί του Ενγκρ του Μαν Ρέι, στο οποίο ο καλλιτέχνης προσθέτει δύο «εφ» στη γυμνή πλάτη μιας γυναίκας, διακωμωδώντας τον ληθαργικό κλασικισμό της Οδαλίσκης του Ενγκρ, ενώ ταυτόχρονα επιτελεί τον δικό του μετασχηματισμό του σώματος. Ομοίως, τα σκηνικά αντικείμενα του Γέρου ξηλώνουν τις ραφές που ενώνουν την αρχαιότητα με το παρόν, χωρίς να λείπει ούτε σ’ αυτή την περίπτωση μια δόση πικρού χιούμορ. Άραγε οι εικόνες του Γέρου αντιπροσωπεύουν στοχασμούς για το ασυμφιλίωτο των δύο αυτών κόσμων; Οι φωτογραφίες δεν είναι τόσο στρυφνές. Είναι παιγνιώδεις και λογοπαικτικές, ακόμα και στο σχολαστικό τους καδράρισμα ή στον πρόσθετο διάκοσμο, την αταραξία του παίκτη του πόκερ. Τα σώματα αυτά νιώθουν άνετα στη σημερινή τους εποχή. Το γεγονός ότι οι αναπάντεχοι φτερωτοί και τριχωτοί σύντροφοί τους δεν μειώνουν τη σχέση τους με την τέχνη των κλασικών χρόνων επιβεβαιώνει την επιδεξιότητα του Γέρου ως φωτογράφου.

ARA H. MERJIAN

From the exhibition “Classicism Subverted” Paris April-May 2005

Ό Δημήτρης Γέρος γεννήθηκε στη Λεβαδιά, κάτω από τη σκιά του Παρνασσού, και το δράμα των ανεμπόδιστων οπτικών εκτάσεων της παιδικής του ζωής τον καταδιώκει σαν ένας ένας ευεργετικός γυφτοδάσκαλος με βιτσιές, ξόρκια προπηλακισμούς και προτροπές - ο μόνος άλλωστε δάσκαλος πού θα είχε, ο ζωγράφος, στη ζωή του. Οδυνηρά αυτοδίδακτος, όπως όλοι οι σωστοί Έλληνες, δίνεται ολόσωμος στο κάλεσμα των Παρνασσίδων τροφών του.

Τα όνειρα των μακρινών αποστάσεων, με τους ανοιχτούς ορίζοντες, με τα υποσκάζοντα βουνά, ύπόφωσκα, πλαισιώνουν τώρα μιαν ανελέητη επίκληση ενός συμβόλου, πού διαρκώς επανέρχεται θεματικά, χωρίς να επαναλαμβάνεται ωστόσο ποτέ: το μήλο. Αυτή η σφαίρα της φυτικής ύλης, ό καρπός εκείνος πού ή μυθολογία του κάθε τόπου και της κάθε εποχής τον συνέδεσε πάντα με το άπιστο, το κακό, το αμαρτωλό, το αποτρεπτικό: (αρκεί να θυμηθούμε το μήλο της Εύας, το μήλο της έριδος, τα τρία μήλα της Αταλάντης, το μήλο του δράκοντα Σούγκ· κάτω από μια μηλιά ήταν τεντωμένο το Χρυσόμαλλο Δέρας, από την Κόκκινη Μηλιά μας ήρθαν οί Τούρκοι). Αλλά το μήλο έχει κάτι και το τροφικό, το χοϊκό, το μεσσιανικό, το σκεύος της εκλογής: το χρυσόμηλο της Κασσιανής, το ξύλο της Γνώσης, το κάρπισμα της Σοφίας.

Ναι, το μήλο· τέλεια σφαίρα, άλλοτε περιέχον, άλλοτε περιεχόμενο. Το μήλο πού χωράει μέσα του μια πόλη, το μήλο πού μια πόλη δεν το χωράει. Το απειλητικό μήλο πού ρίχνει τη δυσοίωνη σκιά του πάνω στο τοπίο, το μήλο πού έγκιβωτίζει τη φύση. Το μήλο, τέλεια σφαίρα, αλλά παρουσιασμένο με μια ανησυχητική, σκοτεινή οπή : κατοικία - ραγάδα του ακοίμητου σκουληκιού πού θα μας φάει όλους, ή τάχα τρήμα για μια εκτίναξη εκβλάστησης, λίκνο του βίου; Πάντως, το μήλο. Ή βιόσφαιρα. Ή έκτροφόσφαιρα. Ή πυροβολόσφαιρα. Ή πλανητόσφαιρα. Ή άθλητόσφαιρα. Άλλα ας σταματήσουμε. Ή ερμηνεία του συμβόλου ανήκει αποκλειστικά στον θεατή. Ό καλλιτέχνης προσφέρει μόνο το ερέθισμα. Τα αλλά είναι λόγια, αγνοήστε τα.

Όμως, ευτυχώς, λόγια δεν είναι μήτε τούτα τα ευρηματικά απαλύματα των χρωματισμών, μήτε οί τόσο ολοκάθαρες επιφάνειες, μήτε ή σίγουρη εγγραφή του αντικείμενου μέσα σε έναν σιγουρεμένο και ασφαλιστικό περίγυρο. Εδώ, έχουμε να κάνουμε με το πράγμα. Αυτό Άλλωστε είναι πού δίνει την χαρούμενη, σχεδόν εκκωφαντική μέσα στη σιωπή της, ευθυμία μιας φαντασίας ταυτόχρονα τόσο παιγνιώδους και τόσο σοβαρεμένης. Και αυτό δείχνει την εκρηκτική χαρά μιας ατελεύτητης, χορευτικής σχεδόν, και όμως αυτοχαλιναγωγημένης δημιουργικότητας. Elan vital, όπως το είπε ό Μπέρξον. "Ας μη λησμονούμε όμως και την ετυμολογία τούτης της πολύπαθης λέξης: Δημιουργία είναι το συνθετικό παράγωγο των δύο λέξεων, Δήμος και Έργον. Όσοι, στα χρόνια της Αθηναϊκής Δημοκρατίας, δεν πήγαιναν να καλλιεργήσουν το χωραφάκι τους, να βοσκήσουν τα αρνιά τους, να φτιάξουν μενιδιάτικα ξυλοκάρβουνα ή λιοπεσίτικο κρασί, μα καθόταν και σπαταλούσαν τις ώρες τους μαστορεύοντας την πέτρα σε γλυπτό, ανακατώνοντας τα χρώματα σε τοιχογραφίες, σκαλίζοντας γράμματα στο κερί ή στη δορά των εριφίων και φτιάχνοντάς τα σωκρατικούς διαλόγους, αυτοί δούλευαν για το Δήμο, για το Λαό, φτιάχνοντας ένα έργο για όλους. Έστω κι' αν αυτοί οι «όλοι» δεν κάναν τίποτα άλλο παρά να τους εμποδίζουν σε τούτη την ανιδιοτέλεια τους.

Αυτή την επαφή με τη ρίζα της προέλευσης της λέξης «Δημιουργία», την ξυπνάει το ατένισμα ενός έργου του Δημήτρη Γέρου. Και τώρα, προειδοποιημένε επισκέπτη, ψάξε και συ να βρεις, μέσα από το σύμβολο, πέρα από το σύμβολο, πίσω του, έξω ή εντός του, μασώντας το ή και αποπτύοντάς το τρεφόμενος ή δηλητηριαζόμενος από αυτό, ψάξε να βρεις τον τρόπο να πραγματοποιήσεις μόνο σου τούτη την αναγωγή. Μπορείς!

Θ. Δ. ΦΡΑΓΚΟΠΟΥΛΟΣ

Κυριακάτικη Δημοκρατία,

Σάββατο 14-3-2020, κριτική της Αθηνάς Σχινά

Δημήτρης Γέρος: Τα αναπάντεχα και οι παραδοξότητες τέχνης και ζωής

Παρά τους φόβους που έχει ενσπείρει η πιθανή και απευκταία βέβαια εξάπλωση του κοροναϊού, ο οποίος είναι η αιτία της αναβολής πολλών προγραμματισμένων πολιτισμικών εκδηλώσεων, μολαταύτα αρκετές είναι εκείνες οι εικαστικές εκθέσεις που ερήμην των συγκυριών πραγματοποιούνται αυτόν τον καιρό, έστω και χωρίς εγκαίνια. Από την άλλη πλευρά, ουδέν κακόν αμιγές καλού ασφαλώς, γιατί το δυσάρεστο αυτό γεγονός της αποφυγής συγκεντρώσεων, δίνει την δυνατότητα να περιοριστούν κάπως οι «κοινωνικότητες» και τα lifestyles, που έχουν αλλοιώσει κι αλλοτριώσει (με τα «πολλά τους μαλάματα», καθώς θα έλεγε και ο ποιητής) το πρόσωπο της τέχνης.

Αν ο κόσμος αποφεύγει να τρέχει στα θεάματα, οι ανθρωπότυποι ωστόσο του Δημήτρη Γέρου – που αυτόν τον καιρό εκθέτει ζωγραφικά του έργα με ακουαρέλες στην Αθηναϊκή Γκαλερί ΔΛ του Δημ. Λυμπερόπουλου – εξακολουθούν στις εικαστικές του συνθέσεις να τρέχουν. Και τρέχουν, δραπετεύοντας από τις καθημερινότητες που έχουν δημιουργήσει και παράλληλα αποφεύγουν, από τους εφιάλτες τους επίσης που τους κυνηγούν, αλλά και από τους διάφορους ρόλους που έχουν επιλέξει και υποδύονται για τον εαυτό τους.

Τις φιγούρες αυτές του Δημήτρη Γέρου, τις αστικά ντυμένες ή γυμνές, που στις πλάτες τους καμιά φορά φυτρώνουν φτερά ή έχουν καρφιτσώσει τις αγωνίες τους, τις βλέπουμε να δρασκελίζουν όνειρα και μονοπάτια καταφυγής, πόθους και παθήματα, χρόνους και λαχτάρες, μνήμες ανεξιλέωτες και τόπους αχαρτογράφητους, πότε ως ρυθμιστές των καταστάσεων κι εξουσιαστές, άλλοτε πάλι ως ρυθμιζόμενοι από κοινωνικές ανάγκες και συστήματα, που εμφανώς ή αδιαφανώς, εκείνα τους εξουσιάζουν. Διωκόμενοι και καταδιώκοντες οι ανθρωπότυποι αυτοί (του γνωστού υπερρεαλιστή ζωγράφου και διεθνώς καταξιωμένου φωτογράφου) είναι πλασμένοι σαν σκεπτομορφές. Αναχωρούν και πάντοτε επιστρέφουν, για να φύγουν ξανά από την φύση που καταστρέφουν κι από εκείνη που διεκδικούν καταστρατηγώντας την ή από την ζωή που έχουν επιλέξει να βιώσουν και ταυτοχρόνως παραβιάζουν τα όριά της. Και τα παραβιάζουν, προκειμένου να σωθούν αφενός από τα αναπάντεχά της, αφετέρου από τις δεσμεύσεις και τις κηδεμονίες της, από τις συνήθειες επίσης στις οποίες έχουν μιθριδατιστεί, αλλά και από τις συμφύσεις που έχουν προκαλέσει σε σχέση με τα παρελθόντα τους, αλλά κι εκείνες που σιωπηλά έχουν υφάνει, μαζί με τις εσωτερικές τους Ερινύες.

Παλαιότερα, είχα διατυπώσει την άποψη, πως ο Δημήτρης Γέρος είχε καταργήσει συνειδητά στην ζωγραφική του την διάκριση ανάμεσα σε υποκείμενο και αντικείμενα, σε αφηγητή και ήρωα θα λέγαμε, αν επρόκειτο για πεζογράφημα ή πρωτοπρόσωπη και τριτοπρόσωπη παρουσίαση καταστάσεων, αν επρόκειτο για θεατρική παράσταση. Την καθαίρεση αυτή των αποστάσεων, που μεταφέρει ο κάθε ανθρωπότυπός του, την παριστάνει ο Δημ. Γέρος στο εικαστικό του προσκήνιο ως σχισματική ταυτότητα μιας τραγικής και ανέστιας ταυτοχρόνως persona, που βρίσκεται σε κατάσταση διαρκούς μετανάστευσης. Η σκεπτομορφή αυτή υποστασιώνει μια φιγούρα που εμφανίζεται ως απορροή του αστικού περιβάλλοντος των μεγαλουπόλεων. Γεννιέται από αυτό το περιβάλλον, εκτρέφεται αλλά κι αποδιώχνεται ως απόβλητο παράγωγο της μαζικής βιομηχανικής παραγωγής, της υψηλής τεχνολογίας και παράλληλα μιας ύποπτης συναλλαγής, που τον πωλεί και τον αγοράζει ανά πάσα στιγμή, γιατί ευδαιμονικά και μεθοδικά τον έχει προ πολλού ευνουχίσει, αφαιρώντας του τις άμυνες και γεμίζοντάς τον παραλλήλως ενοχές.

Στο κείμενο που συνοδεύει την έκθεση αυτή, ο θεωρητικός της τέχνης Dominique Nahas, που δραστηριοποιείται στη Νέα Υόρκη, επιχειρώντας μια ανάγνωση στα έργα του Δημ. Γέρου που εμφανώς θαυμάζει, εκτός όσων σημαντικών στοιχείων εντοπίζει, προσπαθεί να συνδυάσει και να αναδείξει γόνιμες αντιθετικότητες που αυτά περιλαμβάνουν, πέφτοντας εντέλει σε αντιφάσεις ακόμη και σε λανθασμένες διαπιστώσεις. Αναφέρει συγκεκριμένα, πως «αυτή η εικονογραφία, με την διαμεσολάβηση του τυχαίου (!) και της ονειροπόλησης, είναι μια δύναμη ποιητική και συνάμα συμφιλιωτική». Δεν θα παρέπεμπα ποτέ σε τόσο άστοχη παρατήρηση, αν αυτή δεν μου έδινε την αφορμή να τονίσω πως στην δουλειά του Δημήτρη Γέρου, τόσο την ζωγραφική, όσο και την φωτογραφική, ισχύει ακριβώς το αντίθετο! Όλα μέχρι και την τελευταία λεπτομέρεια, είναι τόσο υπολογισμένα και μελετημένα, έτσι ώστε τίποτε να μην είναι τυχαίο.

Άλλο πράγμα είναι να φαίνεται και να παρουσιάζεται κάτι ως αυθόρμητο και τυχαίο κι εντελώς άλλη κατάσταση είναι να ρυθμίζει με τέτοιον τρόπο ο καλλιτέχνης την σύνθεση και το ύφος, την δομή και το σχέδιο, το φως και τον χώρο, τα υλικά και τα χρώματά του, έτσι ώστε να φαίνονται ως απροσχεδίαστα, προκειμένου να αποφύγει την εγκεφαλικότητα. Άλλωστε το τυχαίο και η ονειροπόληση, δεν μπορούν να μετατραπούν σε δύναμη (!) ποιητική και συνάμα συμφιλιωτική (!). Αντιθέτως, όταν οι υπαινικτικές παραδοξότητες που ο εικονισμός του συγκεκριμένου ζωγράφου εμφανίζει στα ζωγραφικά του έργα, μπορούν αντισταθμιστικά να εναρμονίζονται και οριακά να ισορροπούν τις αντιθέσεις τους ανάμεσα στο όνειρο και στην πραγματικότητα, στην συνείδηση επίσης και στο υποσυνείδητο, τότε η παραστατικότητα υπονομεύοντας την εκλογίκευση και καθιστάμενη δίσημη ανάμεσα στις αλήθειες και στις ουτοπίες της, μπορεί ενδογενώς να διαμορφώνει μια ποιητική δυναμική.

Αυτού του είδους η μορφική δυναμική που προανέφερα, μαζί με το ύφος, τις χροιές και την ατμόσφαιρα που στο κάθε έργο καλλιεργείται, εξαρτάται από τους τρόπους που ο καλλιτέχνης θα στοιχειοθετήσει τον συνειρμικό εικονισμό του, έτσι ώστε να παραχθεί ποίηση. Μια ποίηση, που να λειτουργεί πολυδιάστατα κι αινιγματικά, ανάμεσα στην τραγικότητα και στην ειρωνεία, στους γρίφους της ζωής και στην γοητεία του εφήμερου, στην οδύνη της απώλειας και στην έκπληξη του άγνωστου που με ελπίδα κάθε φορά προσδοκάται, ακυρώνοντας προς στιγμήν τους εφιάλτες της ματαιότητας, καθώς η υπαρξιακή αγωνία είναι εκείνη που βρίσκει εντέλει το σωτήριο μονοπάτι για την υπερβατικότητα. Και μάλιστα, στην προκειμένη περίπτωση του Δημήτρη Γέρου, ο υπερεαλισμός είναι το εκφραστικό εκείνο ιδίωμα που συνειδητά ο δημιουργός αυτός το έχει επιλέξει, όχι για τις παραδοξότητες του υποσυνειδήτου στις οποίες δίνει διέξοδο, ούτε για την διασάλευση της δεσμευτικής κι «ανελεύθερης» εκλογίκευσης αιτίου κι αιτιατού, αλλά γιατί με την ελλειπτικότητα του «λόγου» της εικόνας του και με τους υπαινιγμούς της, ο Δημήτρης Γέρος διαμορφώνει μια νέα κάθε φορά μυθοπλοκή. Μέσα από αυτήν, ο θύτης γίνεται θύμα, ο αναχωρητής γίνεται πολιορκημένος και ο φυλακισμένος ελευθερώνεται από κάθε Προπατορική αγκύλωση, ανοίγοντας δρόμους σπαρμένους ωστόσο με την πικρία του τιμήματος της γνώσης, για το κέρδος μιας πορείας που οδηγεί προς άλλες συνειδησιακές κατακτήσεις.

Αθηνά Σχινά

Ιστορικός Τέχνης & Θεωρίας του Πολιτισμού (ΕΚΠΑ)

Σάββας Χριστοδουλίδης

Εικαστικός καλλιτέχνης, Κύπρος 17-11-2014

ΙΣΤΟΡΙΕΣ ΕΝΟΣ ΝΗΝΕΜΟΥ ΚΑΙΡΟΥ

Για να μη σκέφτομαι όλη αυτή την ανηθικότητα και την ηλιθιότητα

όπως και την τόση φρίκη, καταφεύγω όλο και περισσότερο […] στο ιερό αυτό τέμενος όπου δύο θεές στέκονται χέρι χέρι: η αληθινή ποίηση και η αληθινή ζωγραφική

Τζιόρτζιο ντε Κίρικο .

Στέκομαι στην πρώτη και ανυποχώρητη εντύπωση που τα έργα του Δημήτρη Γέρου προκαλούν: την εντύπωση του αμετάκλητου, του ανυποχώρητου, του αδιάλλακτου. Κάθε όν ή πράγμα υπερασπίζεται και γεύεται ασάλευτο τη θέση του. Προσφέρεται παράτολμα σε θέαση από τη μια, ενώ από την άλλη κοινωνεί - παραδομένο σε ατάραχη σιγή - μιαν ακατάλυτη αυτονομία. Στην αρχή της καθ’ολοκληρίαν παράθεσης ακουμπά ο καλλιτέχνης κάθε αφηγηματικό εγχείρημα του. Στα έργα, τα πράγματα προσφέρονται μες’στην ολότητα τους: αληθινά, ακέραια και κραυγαλέα ήπια. Μοιάζουν να γεύονται το πλήρες θεαθήναι. Ανάγονται κατά συνέπεια σε αδιάλλακτα και κραταιά εμβλήματα. Λοφίσκοι, πεταλούδες , σύννεφα-σπερματοζωάρια, κηλίδες και πλοία - μεταξύ άλλων - συνεργούν στην πραγμάτωση αυτού που ο Αντρέ Μπρετόν όριζε ως « θείο τέχνασμα » : μέσο απαραίτητο ή και μεθόδευση για ερμηνευτική διάνοιξη του νόμου του αινίγματος. Η αφήγηση του Γέρου, όπως προανέφερα, είναι αδιάλλακτα παραθετική. Μπορούμε να μιλήσουμε για ζωγραφική που μοιάζει με αινιγματική αφήγηση. Αλλιώς, για ένα εγχείρημα αφήγησης που ιστορεί πτυχώσεις του αινίγματος στη γλώσσα της ζωγραφικής. Το αμφίδρομο αυτό σχηματικό ιδίωμα φιλοξενεί αρχές και ιδεώδη. Απεκδύεται εντούτοις λογικές απολήξεις.

Τα περισσότερα έργα συνιστούν, θα έλεγε κανείς, ιστορίες κατατρεγμού. Ένας άντρας πορεύεται με δρασκελιές γενναίες. Με ένα πόδι γεύεται τη γη και τη σκιά του σώματος που γράφεται στο πέρασμα του. Με ένα χέρι, αιχμηρά ανοίγει δρόμο και ορίζει το φευγιό του. Μοιάζει με άντρα προσκολλημένο σε ποδόμυλο. Ο ήρωας ορμητικά ανακυκλώνει την περπατησιά του. Υπόθεση ψυχοανάληψης; Να γεύεται κανείς τον χώρο και τον χρόνο του με το μυαλό και τις ορμές του εν εγρηγόρσει; Ο ήρωας - Ερμής, πρωτάγγελος και ίσως θρέμμα φτερωτό - ανάγει την εντοπιότητα του σε καθεστώς ψυχογενούς ανάλωσης. Κάτι ανάμεσα στο μάταιο που σημαδεύει το ανθρώπινο και μια αέναη ακατανίκητη ορμή που λούζει κάθε τι θεόκλητο τον ταλανίζουν. Γράφει τη παρουσία του σε αχανείς τόπους ονείρου ή σε δωμάτια ξεγυμνωμένα και κλειστά που κοινωνούν παρόλα αυτά τον έξω κόσμο. Καμία υποψία εγκλεισμού δεν σημειώνεται. Το μέσα διαρρέει και χαρίζεται στον έξω. Και μια συνθήκη εναρμόνισης ανάμεσα σε επουράνιες αξίες και επίγειες αρχές θεσπίζεται και εγγυάται συνεπώς την πολυπόθητη – στον καλλιτέχνη – συμπαντική ολότητα. Κάτι κυριεύει τις εικόνες που τις καθιστά παραχωρητικές ενώ ταυτόχρονα η μίανση μιας συστολής τις καταπνίγει. Οικείες και απόκοσμες συνάμα, άλλοτε πάλλονται και άλλοτε - ατάραχες και άκαμπτες - παγιώνουν. Στη βάση ενός δυαδικού και αντιφατικού ποιείν ορίζεται λοιπόν ο τόπος της αναγκαιότητας του Γέρου. Απλώνεται το βλέμμα και χαίρεται τις νηνεμείς περιοχές της εγκαρτέρησης. Εκτείνεται μέχρι το όριο, το ύστατο σημείο παρεμπόδισης, μια γραμμική περίφραξη συχνά μη αισθητή. Ο Ραίνερ Μαρία Ρίλκε στο Περί του τοπίου δοκίμιο προτρέπει να γίνονται οι τόποι αντιληπτοί εξ αποστάσεως, « ως κάτι μακρινό και ξένο, ως κάτι απόμερο και άστοργο ». Αυτή η αποξένωση, κατά τη γνώμη του, είναι που εγγυάται τη γνώση του τοπίου και που το καθιστά « λυτρωτικό όσο το πεπρωμένο μας » . Αλλά και ο Μπρετόν εξαίρει την καταληπτική ισχύ του βλέμματος και το ευφραντικό συναίσθημα που αυτό συχνά εκλύει. Γράφει: « … δεν αγαπώ τίποτα περισσότερο όσο αυτό που ανοίγεται μπροστά μου ως εκεί που χάνεται το μάτι. Χαίρομαι μέσα σε ένα πλαίσιο μορφών, τοπίων ή θαλασσών, ένα υπέρμετρο νόημα » .

Διάνθισμα μορφικών εκλεπτύνσεων και σιτεμένων στοχασμών συνιστούν τα έργα του Δημήτρη Γέρου. Νοσταλγός και συνάμα πλάστης ενός κόσμου μεταφυσικού, ανάγει τη σύμμειξη επιλεγμένων ετερόκλιτων στοιχείων σε καθεστώς εικονικής αφήγησης. Εξιστορεί μανιέρες και τεχνάσματα. Εξιστορεί τους τρόπους που συχνά μηχανευόμαστε για να μπορέσουμε να διανοίξουμε τη συμπαγή και άθραυστη ιδέα του αινίγματος. « Πως μάθαμε το όνομα του ήλιου ; » διερωτόταν ο Μπρετόν . Πως έμαθε ο Γέρος το άλλο όνομα της πεταλούδας και την λέει ουρανόπεμπτη;

Γιάννης Κοντός:

Ο Καβάφης και τα σώματα

(Τα ποιήματα του Καβάφη στα Αγγλικά. Φωτογραφικό άλμπουμ του Δημήτρη Γέρου)

Αυτοί οι απλοί νέοι άνδρες που σοφά τοποθετούν το σώμα στο φακό του ζωγράφου Δημήτρη Γέρου, είναι αθώοι, χωρίς αμαρτίες και πλησιάζουν τα ποιήματα του Αλεξανδρινού, που δημιούργησε έναν άλλο ουρανό της Ελλάδος. Συνέχεια του αρχαίου θαυμασμού για το σφριγηλό σώμα, για την παλαίστρα, για τα γράμματα και τα όνειρα. Κοιτώ τα σώματα που ερμηνεύουν τα ποιήματα και σκέπτομαι τη φθορά, την άμμο στην κλεψύδρα. Αλλά τα ποιήματα μένουν και θα μείνουν στους αιώνες. Το γυμνό δεν ενοχλεί γιατί μιλά τη γλώσσα του σώματος, τη γλώσσα του παράδεισου. Πίσω από αυτά τα ανθηρά σχήματα ο ήλιος της Αλεξάνδρειας φωτίζει, σκιάζει και λέει την αλήθεια. Τα δάκτυλα, οι ώμοι, τα πόδια, οι μηροί, τα απόκρυφα μέρη (που είναι φανερά) και κυρίως τα μάτια ξεδιπλώνουν το μυστήριο της ζωής, της αφής και του έρωτα -κάθε είδους έρωτα-γιατί, όπως έλεγε ο συγγραφέας Γιώργος Χειμωνάς, ο έρωτας είναι ένας και αδιαίρετος. Οι γέροι που ποζάρουν μαζί με νέους ξεσκεπάζουν το χρόνο, τη διάρκεια και τα μεγάλα ερωτηματικά. Σε μερικές φωτογραφίες ψιλοβρέχει: η νοσταλγία, η λύπη κι ένα μειδίαμα που πέρασε και δεν επανέρχεται. Η βαθιά δεξιοτεχνία και η μεγάλη ευαισθησία του φακού του ζωγράφου Δημήτρη Γέρου δη-μιουργεί ανεξίτηλα πορτρέτα. Πολλές φορές: τα λουλούδια, τα σεντό-νια, το κρεβάτι συνομιλούν με τα σώματα και αναδεικνύουν. Όλες οι φωτογραφίες δεν ερμηνεύουν τα ποιήματα του Καβάφη· τα συνοδεύ-ουν διακριτικά και ψιθυρίζουν μυστικά στο αυτί του χρόνου. Οι φωτο-γραφίες είναι μαυρόασπρες. Έχουν βάθος, γλυπτική και πολλές συνθέ-σεις. Τα χρώματα υπονοούνται διακριτικά και ο κόσμος του Καβάφη αναδύεται ολόσωμος και εφηβικός με την υπόσχεση της αιωνιότητας. Αυτή η φωτογραφική σπουδή του Δημήτρη Γέρου δείχνει τη ζωή, την αθωότητα των ανθρώπων στον παράδεισο και στην ποίηση.

by Lauren E. Talalay

Acting Director and Associate Curator, Kelsey Museum University of Michigan.

Kelsey Museum University of Michigan 2002

DIMITRIS YEROS

Sense and Sensibility

Dimitris Yeros stands as a unique figure in contemporary art. Painter, photographer, poet and performance artist, Yeros bridges these worlds with exceptional originality. He is, however, best known as a painter and photographer, creating lyrical and surreal paintings and provocative and richly textured photographs. Although he approaches these two media from different vantage points, one can detect a painterly eye in his photographs and a photographer's sensibility in his paintings. The results are beautifully crafted and arresting images that beckon the viewer to pause and contemplate the human condition.

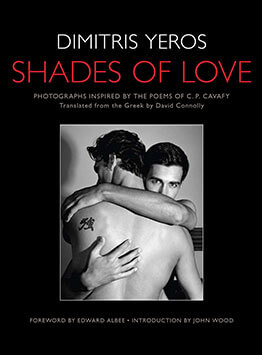

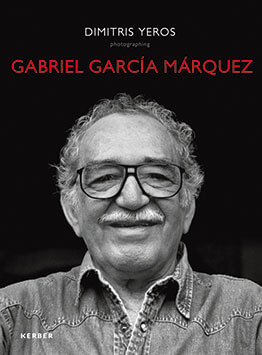

Yeros's most recent work-in-progress is a book of photographs inspired by the eminent Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy. Since his death in 1933, Cavafy has emerged as a symbol of the Greek diaspora, inspiring an impressive array of artists, musicians, and writers. With the exception of Duane Michals, however, few contemporary photographers have used Cavafy's evocative verse to create a body of work. Michals's Homage to Cavafy (1978), is a tribute to the poet, who was forced to hide his homosexuality in a society that condemned such behavior. Michals's subtly erotic photographs, which are intended to be "separate and sympathetic," not illustrative of Cavafy's more homoerotic poems, form a perceptive visual narrative on desire, longing, and the brevity of life.

Dimitris Yeros participates in a very different, but equally penetrating, discourse with the great poet. Yeros and Cavafy form a natural but contradictory pair. Both are Greek, tethered to a rich heritage. Both explore the mysteries of human emotion, eroticism, physical beauty, and nostalgia. Yeros, however, was born 15 years after Cavafy's death and inhabits a society poles apart from Cavafy's turn-of-the century culture. The poet lived at the margins of the Greek world, spending most of his adult life in the city of Alexandria, Egypt. Cavafy's works went largely unpublished during his lifetime, celebrated by just a small coterie of admirers. It was only posthumously that he emerged as a towering figure of the modern period. Yeros, on the other hand, is an internationally recognized artist who travels the globe, returning for several months each year to his home away from home the island of Lesbos. His often whimsical and sensuous canvases embrace the surreal, a world far removed from the supremely tangible, often historically based environs of Cavafy's poetry. Yet, for both the world is eternally layered. Both struggle to eloquently capture the vagaries of life that often transcend full understanding. And, both often situate their works within the resonant spheres of the Mediterranean.

Yeros approaches Cavafy's poems with clarity and directness. He takes well-known people, or less often images of common people and landscapes, and contextualizes them within the story, event, or sentiment limned by specific poems. Individuals are carefully matched with selected poems, establishing a dialectic between the person and the verse.

For example, Yeros pairs the poet Richard Howard with Cavafy's poem "Voices." In that brief and economical poem Cavafy muses about the voices of the dead: "Sometimes they speak to us in dreams/ sometimes deep in thought the mind hears them/ And with their sound for a moment return/ sounds for our life's first poetry-/ like music at night, distant, fading away." Richard Howard is himself a poet, known for his erudite poems and exuberant prose. He is also a celebrated translator, who has brought the "voices" of French writers and poets to the English-speaking world. Yeros places Howard within a seeming mausoleum of photographic portraits-floor to ceiling depictions of famous individuals, Howard's friends, and even a picture of Cavafy, whose photo lies just to the left of Howard. The effect is a mosaic of heads surrounding the bespectacled face of Howard. Although the words of the individuals portrayed in the photographs are literally mute-they cannot speak to us-the scene seems to echo with utterances. One can almost hear the "voices" of the people entombed in the photograph.

Equally compelling, although tinged with humor, is the photo of the artist Arman. Arman, an important modern "pop' artist known for innovative sculptures built of sliced, squashed, and burned objects from everyday life, is paired with the poem "Sculptor of Tyana." The sculptor of the poem is an imaginary artist of the Roman Empire who works in Tyana, an ancient city in Cappadocia. The sculptor speaks of his successes and his endeavors, the great gods and goddesses he has lovingly sculpted as well as the eminent Roman senators who have commissioned his work But, he recalls, his favorite work, "wrought with the utmost care and feeling," is

a young Hermes. Yeros's recasts the poem into a witty and modern commentary. Arman sits in a florid robe holding a photograph depicting his own creation of Hermes. Arman's Hermes is not, however, a "classical" rendition but rather an updated version of this winged god, constructed from modern bricolage.

Finally, Yeros creates his own homage to Duane Michals in a photographic "triptych" linked to Cavafy's poem "The Next Table." The poem is set in a "casino" with the writer, an old man, gazing at an adjacent table. At that table sits a young and strikingly handsome male. Looking at the man seated adjacent to him, the older man begins to reminisce about a much earlier encounter with another young lover. He then imagines that he sees, under the clothes of the arresting youth to his side, the body of his erstwhile lover, "the limbs I loved, naked". Yeros's "triptych" unfolds like a narrative-much in the way that Michals uses photographic story-telling-to expose the imaginings of the old man. An older (fully clothed) man glances, first directly, then distantly, then almost secretly at a naked youth lounging at the table next to him. The young man looks dreamily into the distance, oblivious to the stares of his neighbor. The older man is, in fact, Duane Michals and the body of the naked man a reference to the kinds of bodies that filled the pages of Michals's Homage to Cavafy.

Yeros's Cavafy-inspired images offer us both food for thought as well as a moving aesthetic experience. Each photograph is a carefully composed beautifully crisp black and white rendering, filled with details. The images are varied-some celebrate the nude male body, others a chance erotic encounter, still others the interior of a workshop, a sensuous landscape, or a moving view of a country village and its men. The viewer is invited to contemplate the links between poetry and art, to question

why each image was selected, and to consider how the two artistic forms intertwine and resonate. Cavafy once wrote that "Art knows how to shape forms of Beauty, / almost imperceptibly, completing life ". Dimitris Yeros has indeed brought us an art that helps complete life.

Πλάτων Ριβέλης:

Η αλήθεια τού φωτογραφικού γυμνού

(D. Yeros, Θεωρία Γυμνού, Πλανόδιον)

Τα Νέα (Ένθετο Πρόσωπα, 1999)

Το γυμνό είναι ένα προσφιλές θέμα των ζωγράφων και ένα απαραίτητο μάθημα στις σπουδές των καλών τεχνών. Η φωτογραφία το κληρονόμησε από τη ζωγραφική και, παρόλο που δεν μπορεί να τής προσφέρει τις ίδιες υπηρεσίες, το χρησιμοποίησε με μεγάλη συχνότητα και με αντιστρόφως ανάλογη ποιότητα. Το φωτογραφημένο γυμνό μπορεί να μην παρουσιάζει ιδιαίτερες τεχνικές δυσκολίες, αλλά, σε αντιστάθμισμα, θέτει σχεδόν ανυπέρβλητα εμπόδια θεματικού χειρισμού και περιεχομένου. Για να γίνει αυτό αντιληπτό, αρκεί να σκεφτεί κανείς πόσο ευκολότερα δέχεται να ποζάρει για έναν ζωγραφικό πίνακα παρά για μια φωτογραφία. Η δύναμη τής φωτογραφικής αληθοφάνειας, που τρομάζει ή αποτρέπει αυτόν που θα βρεθεί γυμνός μπροστά στον φακό, είναι αυτή ακριβώς που πρέπει να χρησιμοποιήσει ο φωτογράφος για να υπερβεί το ήδη φορτισμένο θέμα τού γυμνού. Η δύναμη τής παρουσίας τού φωτογραφημένου γυμνού υποσκελίζει τον φωτογράφο, ο οποίος, ακόμα και όταν αντιλαμβάνεται ότι δεν μπορεί να την αγνοήσει, την καλύπτει συχνά πίσω από προφανείς και πάντα αδύναμες υπεκφυγές. Γυμνά δήθεν πλαστικής αξίας με την ελπίδα ή το πρόσχημα να αναιρεθεί η γυμνή τους πρόκληση, γυμνά με σχηματική αφαίρεση όπου τα τμήματα των κορμιών γίνονται προσχήματα φωτοσκιάσεων, και γυμνά που χρησιμοποιούνται ως φορείς στρατευμένων μηνυμάτων.

Η ξαφνική απελεύθερωση (και μετέπειτα μόδα) τού ανδρικού γυμνού (θέματος ακόμα δυσκολότερου από το γυναικείο), που εκφράστηκε κυρίως μέσα από ομοφυλοφιλικά φωτογραφικά μανιφέστα, αντί να μας δώσει εικόνες αληθινές, βγαλμένες μέσα από ερωτισμό, βία και πιθανόν καταπίεση, μας έδωσε αντιθέτως καρτποσταλικές και σχηματοποιημένες εικόνες, όπου το μέγεθος των γεννητικών οργάνων προκαλούσε μεγαλύτερη θυμηδία από ερεθισμό ή τρόμο. Τα περισσότερα από αυτά τα γυμνά υπήρξαν από κάθε άποψη ανώδυνα και κατά συνέπειαν αδιάφορα. Οι γυμνοί άντρες δεν διέφεραν σχεδόν σε τίποτα από νεκρές φύσεις. Τα σώματά τους, συνήθως ταυτόσημα με τα πρότυπα τής μόδας και τής διαφήμισης, «κοσμούσαν» δίκην ανθοδοχείων βάθρα και φόντα στο πλαίσιο μιας αισθητικά καθησυχαστικής ωραιοποίησης. Η διακοσμητική τους διάσταση υπερείχε κατά πολύ τής δήθεν ανατρεπτικής γύμνιας τους.

Ο γνωστός ζωγράφος Δημήτρης Γέρος αποφάσισε εδώ και μερικά χρόνια να δοκιμάσει τις ικανότητές του και στη φωτογραφία. Και καταπιάστηκε με ένα από τα δυσκολότερα θέματα, το αντρικό γυμνό, δίνοντάς μας ένα φωτογραφικό λεύκωμα με τον τίτλο "Θεωρία γυμνού". Ο τίτλος αυτός σε συνδυασμό με τον τρόπο αντιμετώπισης των γυμνών σωμάτων δείχνει ότι ο Δημήτρης Γέρος επιχειρεί συνειδητά μια μετάβαση από την κλασική αντιμετώπιση τής ζωγραφικής προς μια μεταμοντέρνα φωτογραφική αισθητική τής περασμένης δεκαετίας. Η άψογη τεχνική του όμως δεν ήταν αρκετή για να καλύψει τις αδυναμίες του σε σχέση με το περιεχόμενο, πολλές από τις οποίες σχετίζονται με όσες αναφέρονται πιο πάνω. Είναι πιθανόν η ολιγόχρονη τριβή τού γνωστού ζωγράφου με τη λειτουργία τού φωτογραφικού μέσου, σε συνδυασμό με ενδεχόμενες αναστολές του μπροστά σε μιαν απόλυτα ειλικρινή αντιμετώπιση τού γυμνού, να είναι υπεύθυνες για αυτές τις εικόνες των ανδρικών «κλισέ», που πολύ συχνά μας θυμίζουν μασκαρεμένο ή «ντυμένο» γυμνό, και που, χωρίς να αγγίζουν την μοναξιά και την βία των γυμνών μελών και των γυμνών βλεμμάτων, δεν φτάνουν καν στην προκλητική έστω γελοιοποίησή τους, αν υποθέσουμε ότι υπήρχε τέτοια πρόθεση.

Για τούς παραπάνω λόγους ήταν μεγάλη η χαρά και η έκπληξή μου όταν ήρθε στα χέρια μου το δεύτερο φωτογραφικό λεύκωμα τού Δημήτρη Γέρου («Περιόρασις»), με μια τελείως διαφορετική φωτογραφική προσέγγιση (η συμβολή τής Νατάσας Μαρκίδου που ανέλαβε το editing πρέπει να ήταν καθοριστική). Σημειωτέον ότι η έκδοση επιχορηγήθηκε από το Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού. Είναι γεγονός πως υπάρχουν αντιφάσεις και ανισότητες μέσα σ'αυτό το βιβλίο, τόσο σε επίπεδο θεμάτων όσο και χειρισμού τής φωτογραφικής γλώσσας. Αλλά διαφαίνεται πρώτον μια πιο ουσιαστική αναζήτηση τού ίδιου τού φωτογραφικού μέσου, και παράλληλα, κάτι ακόμα πιο σημαντικό, μια ειλικρίνεια, ένας αυθορμητισμός και μια έλλειψη επιτήδευσης που ταιριάζουν απόλυτα στην ίδια τη φύση τής φωτογραφίας. Μερικές εικόνες είναι αλήθεια πως μοιάζουν φωτογραφικά άγουρες, σαν αθώα βήματα σε έναν καινούργιο κόσμο, χωρίς γι αυτό να είναι κακές, αλλά και χωρίς να κερδίζουν τον θαυμασμό ή να γεννούν τη συγκίνηση. Άλλες όμως, και αυτές πρέπει μάλλον να χρεωθούν στην ώριμη καλλιτεχνική ηλικία τού δημιουργού, είναι πιο σύνθετες και ουσιαστικές. Κάτι μάλιστα ενδιαφέρον είναι ότι μερικά από τα λίγα πορτραίτα που περιλαμβάνονται αποπνέουν πολύ μεγαλύτερο αισθησιασμό και καταδεικνύουν πολύ γνησιότερο φωτογραφικό αισθητισμό από τα παλαιότερα γυμνά, και, το κυριότερο, με έναν ιδιαιτέρως υπαινικτικό τρόπο.

Η σχέση τού Δημήτρη Γέρου με τη ζωγραφική μάλλον θα παραμείνει πρωταρχική και προνομιακή. Εν τούτοις με χαρά βλέπω ότι η δύναμη τής φωτογραφικής αμεσότητας, σε συνδυασμό με την ευκολία τής φωτογραφικής τεχνικής, προσελκύουν όλο και περισσότερους δημιουργούς, που προέρχονται από διαφορετική περιοχή καλλιτεχνικού ενδιαφέροντος. Οι καλλιτέχνες αυτοί χρησιμοποιούν τη φωτογραφία πότε σαν στοιχείο εμπλουτισμού τού καλλιτεχνικού τους προβληματισμού, πότε σαν μέσον απεγκλωβισμού τους από δημιουργικά αδιέξοδα, και πότε σαν αναζωογονητικό παιχνίδι στην αυστηρή πορεία τής δικής τους τέχνης. Η δύναμη τής φωτογραφίας είναι ότι μπορεί να επιτρέπει και αυτήν ακόμα τη χρήση της, αρκεί όσοι την χρησιμοποιούν έτσι να σέβονται την ιδιομορφία της. Ο Δημήτρης Γέρος το έκανε. Το μέλλον θα δείξει αν η φωτογραφία τον έχει κερδίσει με έναν πιο μόνιμο τρόπο.

Yannis Kontos

THE DARK WAFT OF AIR AND THE FREEDOM OF THE SKY IN THE PAINTINGS OF DIMITRIS YEROS

This bed of red, how it covers Yeros’s landscapes, as he looks out of his colour window, at the clouds and that volcano in the distance. A black chasm, and a bird trying to give a voice to the silent black. Rose fields and mountains hanker for perfume and kisses. The painter will hunt birds with a net across the nearly blue, surrounded by a landscape of faintly outlined mountains and a lake. The fiery volcano is always there, as if waving a handkerchief to the sky. With his greys, silvers, browns and reds (and variations thereof) Yeros creates a peculiar surrealism which, in his dream, touches on naturalism. And that red bird (with just a touch of black on its feathers), with many smaller birds inside it, brings the world closer. In Yeros’s painting, people run, animals are immovable and landscapes are ever changing, as if seen through a kaleidoscope. Often the blue colour together with a dark green will blow the composition sky-high. Here even the fishes glide through the air. In the background a landscape seeks to enter our lives. A hot-air balloon flies over deserted places, looking proud and beautiful. The artist’s paintings are poems complete with many meanings and allusions. An apple is the world with its shadow, and a sky that is waiting. All of the painter’s doors and windows always lead us to surprises. You could call them dreams, but they are the only absolute reality. Furthermore, this is what Art –and its consolation– is. I would also call the painter erotic, because he transmits this feeling without showing it. How a box with a forest inside it is flying – a composition clearly surrealistic and sparkling. Successive landscapes are swirling around the painter and he calmly captures them on canvas. A kitten over and outside the composition of a painting is looking at the viewer and into the composition: a storm, the sky, a red boat whistling. How the artist leafs through the landscapes, as if reading a children’s book. Because that’s how a child understands the world and plays with it. A red sea over the grass and a house; elsewhere, a red meadow and water and running dreams. Yeros’s trees are not imaginary. If you look at them long enough as part of nature, they will be transformed and lure you to reality.

I shouldn’t forget how Yeros also practises photography with success; it has become his other reality. Of course he is a poet who engages in a back-and-forth with gradations of light. I too walk in Dimitris Yeros’s Art and read our lives, our loves and our imagination, which cannot be contained anywhere.

Apart from a few restaurateurs in England and America, Mr Yeros is the only Greek gentleman that I have ever known, but I’ve always been dimly aware that, as a nation, the Greeks have been consumed by a passion for the human body – so much so that, during its heyday, Athens must have looked like an outfitter’s window during a weekday strike. This book at first appears to confirm this ancient belief but, as one turns the pages and the postures of the models become more and more bizarre, one realises the whole idea is being deliciously satirised – a thoroughly entertaining book.

Quentin Crisp

on the book Theory of The Nude

by Paul LaRosa essay from the edition of 21st , 2004

Chiseled Tableaus: The Nudes of Dimitris Yeros

In a moment of unadorned melody--a fragment of birdsong, a Chopin Prelude--the cords within us bend and turn. Time suspends, and from a single nuance, a world unfolds. The solitary nude, pure and unambiguous, is a similar melody, one keyed to beauty and simplicity, a rhythm in which we move in unison. In lowered eyes our desire is merged; from line and limb we quarry the substance of life and love. Each gesture of the body is a moment both intimate and vast, a summation of sense and the lineament of thought.

Dimitris Yeros captures such moments in lyrical photographs that celebrate the beauty of the male body. His nudes distill an unspoiled essence and vitality, discovering gestures and nuances in the body that are infinitely revealing and self-renewing. In their presence, time seems to melt away, and a world of wonder is disclosed, a world scaled both to intimacy and to universality, in which spirit and flesh harmonize. Staged to face us directly, Yeros' nudes are palpably real and teeming with presence--breathing, blinking, pulsing--but at the same time they glow like deities newly imagined. They awaken us to destinies of love and desire, to origins and intangible essences, and in their curves resides the intoxication of instinct. Lucent and visional, they seem brought from the sun, caught by stars, and bent by the moon.

Acclaimed as a painter and photographer, and widely exhibited at home in Greece and abroad, Yeros has also produced sculpture and poetry, and is one of the first video artists. All is concentrated in a pursuit of beauty nourished by an amazement for life, an adulation of youth, and a clear and abundant eroticism. Purity and immediacy define his work, and a fulsomeness that is achieved through clarity, simplicity, and play. Yeros' sensibility is ludic and intuitive, embracing the unexpected through gently surreal arrangements, peculiar combinations that imbue his art with originality and an inherent sense of joy--a joy akin to a child who suddenly runs simply because it is possible, for whom movement precedes purpose. Yeros' photos are governed by the same spirit of openness and spontaneity. They may be staged, but they also seem discovered in their own making. They preserve the ephemeral and entrust themselves to the moment, exuberantly.

This is not to say that his work lacks depth or refinement. On the contrary, it is as contemplative and exquisitely layered as it is simple and celebratory, and it innovates a genre choked with solipsistic gestures, too often bereft of substance, feeling, or originality. A lustrous quality permeates Yeros' prints, with tonal contrasts that are richly suggestive, neither austere nor distancing. Symmetrical and precise, with direct and absolute perspectives, his images of nude males appear as chiseled tableaus, and yet their sculpture belies a natural rhythm, a nimbleness and flux. From darkened chambers that resemble both deep pools and the broad canvas of dreams, figures emerge and assert themselves, irradiant and reborn. Fingers uncurl and extend, clutching sides and grasping feet, quizzically exploring the contours of the body, as if each muscle and bone harbored its own hue, as if the body were a kind of mandala. In these postures Yeros crystallizes moments in which the body is a threshold to self-discovery.

On one hand his nudes, statuesque and ennobled, partake of a tradition of Classical sculpture. Rendered in elongated lines, they appear like marbled forms lit from within, kouroses gilded by fire, uneroded and quintessential. Often they rest on draped tables and pedestals, displayed like frescoes or altarpieces, elevated as icons and artful marvels. We recognize a Classical tradition at work, albeit one that is innovated and revivified. Surreal flourishes abound, maverick flights of the imagination that disrupt our expectations. A boy's torso is covered in snails. The elegant supine pose becomes an arching sprawl, unsure of conclusion. Twisting limbs and leaning postures imitate the symbols and forms of language--alphabets, zodiacs, arabesques. At times, the angled placement of the body seems to suggest the machinations of an unseen puppeteer at work in the background. But the figures are too sensuous to represent dolls, too alive and protean and with gestures too expansive to stand as symbols for the workings of fate. Rather, it is as if his models were released from the temples into the world of the flesh, in which they find themselves vexed by ardor and a newfound freedom, spellbound by a nascent awareness of the body. Their movements are orchestrated yet informal, compelled forth as tides by the cycles of the moon.

A melodious and organic quality keeps these photos natural and intuitive. The props which accompany his nudes seem chosen as Mediterranean icons of simplicity and bounty, resonances of life at its most elemental: apples and lavender, jugs for water, sheaths and wooden tables. Sometimes Yeros pairs his nudes with animals, establishing a kinship that underscores their earthiness and reaffirms our bond with the natural world. In other instances his figures seem animalistic themselves, poised to pounce, transfixed by rut. Issued forth from primal movements and the rudiments of life, Yeros' work is generative and embryonic. It is not exiled from nature, but resident at the very core. I liken it to a pearl brought forth from the depths of the ocean: unique, whole, sensuous and luminescent.

Nothing is decorative or superfluous in Yeros' photographs, and at the same time, nothing is overtly conceptual; the images are essentially associative and imaginatively layered. In one mesmerizing photo, a naked youth, wide-eyed and content, is covered in snails and garlanded with ivy. Painterly and serene, the image is an inspired reinterpretation of the still life banquet, a curious reworking of familiar signs of bounty. But Yeros transcends the rules of any formal game, harnessing an energy that propels the image into the realm of the visionary and the erotic. Like some mythic being, the boy appears newly sprung from the clay of the earth, a living embodiment of the creative force of nature. He emanates a sexuality that is steady and harmonious, a magnetism blended from his tensile limbs, his balanced posture, even from the wet snails that trail across his skin like a succession of kisses. Yeros speaks eloquently to the dynamism of nature, its richness and juvenation. He locates the fantastic within the real, the spirit within the flesh, and as in much of his work, they culminate in an eroticized image of a beautiful boy, an evocation of youth as the sensuous body of the world, fertile and enfolding. We see it again in his photograph of a beautiful young peasant, flaxen-haired and with lips gently parted, who sits naked on a cropping of rocks under a moon-bright sky, encircling a clay urn with delicate hands--a radiant image draped in a mood of expectancy and offering, far removed from any Orientalist vision of exotica. The boy's languorous gaze and the lush chiaroscuro recall the seductiveness of Caravaggio. The image is powerfully erotic, timeless, and peaceful, threaded by a dream of desire and eternal youth. Here is Antinous, the teenage lover of Hadrian, whom Fernando Pessoa immortalized in verse: young and golden-haired, and with "eyes half-diffidently bold"; a "flesh-lust raging for eternity," in whose presence "thou wouldst tremble and fall."

The charged eroticism of Yeros' work often rests in dualities that are skillfully balanced: stillness and motion, the hidden and the exposed, the visionary and the vernacular. A photograph of a boy standing naked, arms outstretched and shielding his body with an opaque curtain, strikes us by an understated yet pronounced complexity. The image is a potent, tactile embodiment of lust and temptation, and at the same time it bestows a sense of innocence and evanescence. Yeros' veil, fluid and impermanent--a counterpoint to the immotile stance and stare of the boy--brings light out of darkness, but it also returns us to a world of secrecy and untapped desire. In its folds seem to lie the currents of the boy's inner world--hope and longing, emotional life, love and sex. More mirror than barrier, and with a dreamy texture that summons contemplation, it harnesses our thoughts as well, a gateway to reflections on the quixotic nature of desire and the passing of time, and the irreconcilable exchange between what is attainable and what forbidden, in which all our lives dwell.

Look at his serpentine image of dark-eyed youth, a male Salome with arms raised and body stretched--a brooding, enthralling depiction of male. We recognize a sexuality that is all-encompassing, that translates the full range of human emotion and experience. It is at once calm and devouring, lyrical and raw, and it seizes on all the senses.

For Yeros, love, beauty and desire are celebrated as equal feasts, sustenances drawn from an essential world of plenty. They nourish his art and instill it with sentience and significance. Rapturous and alive, his nudes are keyed primarily to our senses: they stir and reverberate; we shiver, sigh, and tremble. But they also incarnate the fundamental rhythms of nature, like poems tracing paeans to the interconnectedness of life, its abundance and endless possibilities--as if anchored, in "delicious solitude," in the same pungent natural world of Marvell's "Garden." Their erotic presence fuses the earthly with the ethereal, sex with spirit and sublimity, and it speaks to a kind of perpetual wonder and veneration that is deeply and commensurately felt. It became all the more apparent when, as I sat writing this essay one February morning, I noticed a strange and beautiful confluence of events outside my window, a phenomenon I have rarely glimpsed: a dense curtain of descending snow, and the sun burning bright through shifting clouds, igniting the air. I stopped my work and stood outside, a captive witness to Nature's caprice--an occurrence unique and resplendent, both detailed and immense, still and dynamic, showing a world wending toward harmony. "Wedding of foxes" it is called in Japan. When the snow stopped I returned to my table, and once again looked at beautiful Greek nudes. Surely Dimitris Yeros would be inspired by such a sight, and would understand, who captures the same resplendent world, provokes the same sensations in his glorious photographs.

And you must see and accept this world,

THIS

small, this great world.

Dimitris Yeros is unique in the world of art for he is both a great painter and a great photographer. Most painters who have also been photographers have not approached photography as an original means of artistic expression. They have used photographs as they would sketches and created them as studies for what they consider their most serious work. The resulting images are, therefore, more interesting as artifacts of the creative process than as works of art. In a few rare cases, those of painters Thomas Eakins, José María Sert, Alphonse Mucha, Franz von Stuck, Frank Brangwyn, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, their photographs are occasionally powerful works of art in their own right. However, one can still see --except in the case of Eakins-- that the photograph was always merely a means to an end, a brilliant drawing in light that served to aid in the creation of a painting. This is understandable because seeing with a photographer's eye and seeing with a painter's eye are two distinctly different kinds of vision which demand two distinctly different kinds of craft. It is the same with poetry and prose. Both are literary arts, but how many great poets are also great novelists? There are hardly any, and there are only two great painters who have also been great photographers--Man Ray and Dimitris Yeros, two artists who actually have much in common.

Yeros, just as Man Ray did, approaches his twin arts from radically different positions so that his paintings look nothing like his photographs. Both artists developed an aesthetic of photography distinct and separate from their aesthetic of painting. In photography Yeros is an acknowledged masters of the nude, as was Man Ray, and his photographs, like Man Ray's, are primarily driven by beauty. They immediately appeal to the senses and to the emotions. Yet his paintings, again like Man Ray's, are surreal and reach far beyond reality, beyond the world of senses and the flesh. Though their appeal is as immediate as the appeal of his photographs, it is an appeal to the intellect as it tries to understand and make sense of what he is showing us. And finally the paintings do make very good sense and become quite clear. But initially Yeros's paintings also turn sensual in their appeal because the mind does not worry with making ‘sense’ of them and realizes that much of their ‘sense’ lies buried in their rich sensuality --in their juxtapositions of startling imagery and manipulations of color as shimmering and delicate as Mark Rothko's.

A photographer is always restrained by the world, by what actually exists, even if it is a strange construction or composition of his own invention, as some of Yeros's nudes are. A photographer, therefore, must either record or manipulate Nature, but a painter can invent it. He, unlike the photographer, is never restricted by the limits of his eye; he is only confined by the limits of his own imagination. While a photographer must construct his art from what is, a painter can deal with what never was. And that is the world Yeros gives us, a world as rich as his own boundless imagination, a world of exuberant flowering.

One might ask, but why create a world that is not real, a world that only resembles reality. It is often the case that a resemblance to reality will speak with greater force and truth than the reality we are used to seeing. Those things that daily pass before our eyes and our minds finally do not register with us, and we forget even how to see them. It often takes a jolt or a shock to make us actually stop and see something and think about it, and that is what the paintings of Dimitris Yeros give us--a visual shock that forces our minds into reflection.

Look at these strange paintings of Yeros carefully for a moment and consider what it is we are actually seeing, what it is that he has created to delight our eyes and give our minds something to reflect upon. We see things we know well, the most important things of our lives and the most basic things of life on earth: trees, leaves, apples, thorns, birds, wind, water, clouds, blue sky, animals, mountains, and volcanoes. But stop and consider the very words themselves: trees, leaves, apples, and so forth. They are among the most existential nouns of any language. They are the nouns that name the things that let us know we are alive on a living planet.

What about the volcanoes, one might ask? Aren't volcanoes ominous images? Of course, and they have certainly affected the history of Greece, but they are also proof of the planet's ongoing life and a part of the breathing, stirring world of rain, clouds, and wind. There is very little of the modern technological world represented in Yeros's paintings because most everything that world extols, bows down to, and worships is less important than the great gifts of life itself--wind and leaves, rain and falling apples. In his exuberant world Yeros makes only two mild concessions to technology. He needs a means of transport through his much loved blue skies and through the earth's blue waters, and so we sometimes find dirigibles and steamboats in his work. Zeppelin had perfected the dirigible by 1901, and the steamboat was a late eighteenth/early nineteenth century invention, so both of these inventions predate the watershed year 1914, the real beginning of the disastrous twentieth century, not only the bloodiest century in the world's history, but also the century in which we became more divorced from Nature than ever before. As we look at these paintings of Dimitris Yeros and consider them, the more we come to realize that they are Yeros's own rapturous hymns to Nature. And in spite of their strange and surreal juxtapositions, they are as classical at heart as antiquity itself.