And you must see and accept this world,

THIS

small, this great world.

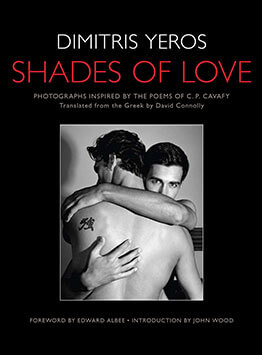

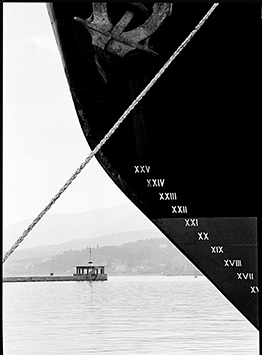

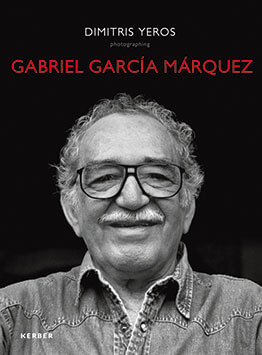

Dimitris Yeros is unique in the world of art for he is both a great painter and a great photographer. Most painters who have also been photographers have not approached photography as an original means of artistic expression. They have used photographs as they would sketches and created them as studies for what they consider their most serious work. The resulting images are, therefore, more interesting as artifacts of the creative process than as works of art. In a few rare cases, those of painters Thomas Eakins, José María Sert, Alphonse Mucha, Franz von Stuck, Frank Brangwyn, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, their photographs are occasionally powerful works of art in their own right. However, one can still see --except in the case of Eakins-- that the photograph was always merely a means to an end, a brilliant drawing in light that served to aid in the creation of a painting. This is understandable because seeing with a photographer's eye and seeing with a painter's eye are two distinctly different kinds of vision which demand two distinctly different kinds of craft. It is the same with poetry and prose. Both are literary arts, but how many great poets are also great novelists? There are hardly any, and there are only two great painters who have also been great photographers--Man Ray and Dimitris Yeros, two artists who actually have much in common.

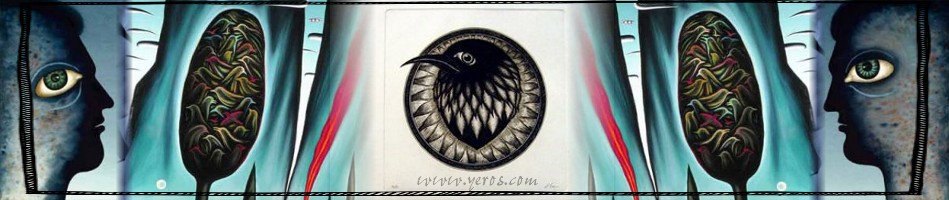

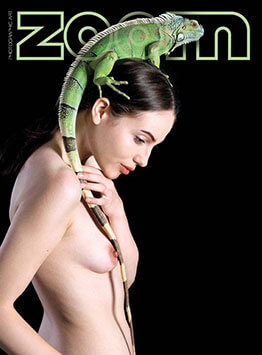

Yeros, just as Man Ray did, approaches his twin arts from radically different positions so that his paintings look nothing like his photographs. Both artists developed an aesthetic of photography distinct and separate from their aesthetic of painting. In photography Yeros is an acknowledged masters of the nude, as was Man Ray, and his photographs, like Man Ray's, are primarily driven by beauty. They immediately appeal to the senses and to the emotions. Yet his paintings, again like Man Ray's, are surreal and reach far beyond reality, beyond the world of senses and the flesh. Though their appeal is as immediate as the appeal of his photographs, it is an appeal to the intellect as it tries to understand and make sense of what he is showing us. And finally the paintings do make very good sense and become quite clear. But initially Yeros's paintings also turn sensual in their appeal because the mind does not worry with making ‘sense’ of them and realizes that much of their ‘sense’ lies buried in their rich sensuality --in their juxtapositions of startling imagery and manipulations of color as shimmering and delicate as Mark Rothko's.

A photographer is always restrained by the world, by what actually exists, even if it is a strange construction or composition of his own invention, as some of Yeros's nudes are. A photographer, therefore, must either record or manipulate Nature, but a painter can invent it. He, unlike the photographer, is never restricted by the limits of his eye; he is only confined by the limits of his own imagination. While a photographer must construct his art from what is, a painter can deal with what never was. And that is the world Yeros gives us, a world as rich as his own boundless imagination, a world of exuberant flowering.

One might ask, but why create a world that is not real, a world that only resembles reality. It is often the case that a resemblance to reality will speak with greater force and truth than the reality we are used to seeing. Those things that daily pass before our eyes and our minds finally do not register with us, and we forget even how to see them. It often takes a jolt or a shock to make us actually stop and see something and think about it, and that is what the paintings of Dimitris Yeros give us--a visual shock that forces our minds into reflection.

Look at these strange paintings of Yeros carefully for a moment and consider what it is we are actually seeing, what it is that he has created to delight our eyes and give our minds something to reflect upon. We see things we know well, the most important things of our lives and the most basic things of life on earth: trees, leaves, apples, thorns, birds, wind, water, clouds, blue sky, animals, mountains, and volcanoes. But stop and consider the very words themselves: trees, leaves, apples, and so forth. They are among the most existential nouns of any language. They are the nouns that name the things that let us know we are alive on a living planet.

What about the volcanoes, one might ask? Aren't volcanoes ominous images? Of course, and they have certainly affected the history of Greece, but they are also proof of the planet's ongoing life and a part of the breathing, stirring world of rain, clouds, and wind. There is very little of the modern technological world represented in Yeros's paintings because most everything that world extols, bows down to, and worships is less important than the great gifts of life itself--wind and leaves, rain and falling apples. In his exuberant world Yeros makes only two mild concessions to technology. He needs a means of transport through his much loved blue skies and through the earth's blue waters, and so we sometimes find dirigibles and steamboats in his work. Zeppelin had perfected the dirigible by 1901, and the steamboat was a late eighteenth/early nineteenth century invention, so both of these inventions predate the watershed year 1914, the real beginning of the disastrous twentieth century, not only the bloodiest century in the world's history, but also the century in which we became more divorced from Nature than ever before. As we look at these paintings of Dimitris Yeros and consider them, the more we come to realize that they are Yeros's own rapturous hymns to Nature. And in spite of their strange and surreal juxtapositions, they are as classical at heart as antiquity itself.

A viewer, however, might wonder about the strange shapes flying through the air in so many of Yeros's paintings. The viewer could certainly recognize birds and fish and trees from the natural world about him, but these strange shapes initially strike a person as something no one has ever before seen. The shape is clearly Yeros's most important symbol, an image he has used for years in painting after painting. It appear in much of his sculpture and medalic art and in over a third of the paintings in the book D. Yeros (Athens, 1997). These rich and potent forms suggest and resemble several things--clouds, of course, because they are floating in the sky. But because the shapes bend their tails in some of Yeros's paintings and sculpture, they suggest something living, and we naturally think of sperm, which also makes us reflect upon their phallic shape. However, they also resemble the fish that fly through the air in some of his paintings, and even the heads of some of his great clusters of birds, and the tip ends of his thorns. This shape seems to unite much of Yeros's imagery and blend it into the sexual and creative. It is as if this shape is both the great mystery of Yeros's paintings and the great mystery of the living world.

Once long ago that mystery was shaped like the features of Olympian gods, but in the exuberant flowering world of Yeros it speeds through the wind and blue skies bringing rain, impregnating nature and transforming into thorn, fish, bird, and man's sexual and artistic creativity both. It is the life force itself. It is Nature's spark and the spiritual energy of the earth. Yeros's vision is finally not merely a hymn to Nature but a hymn to all Creation. And again the words of Elytis come to mind, words deeply suggestive of the imagery of Yeros. In the final stanza of his ‘Ode to Santorini’, Elytis wrote:

In the proclamation of the wind, flash out

That new and perpetual beauty

When the three-hour sun rises aloft

Totally blue, playing the harmonica of Creation.

The harmonica of Creation - it is an instrument that Dimitris Yeros has mastered well.

John Wood is a poet and an art historian who has wan major prizes for his work in both fields. He is the author of four books of poetry and sixteen volumes of criticism and history. He curated the 1995 Smithsonian Institution and National Museum American Art exhibition Secrets of the Dark Chamber and is the editor of 21st: The Journal of Contemporary Photography.