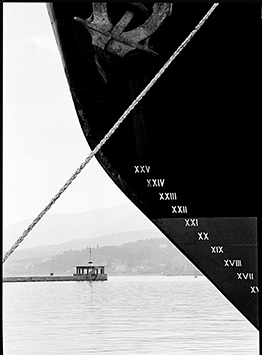

When an artist works in two different genres, one naturally looks for the links between the two different kinds of art he makes. Dimitris Yeros is a very individual painter, with an instantly recognizable style. He is also an immensely skilled photographer, whose images of the nude have the flawless poise of Greek classical sculpture.

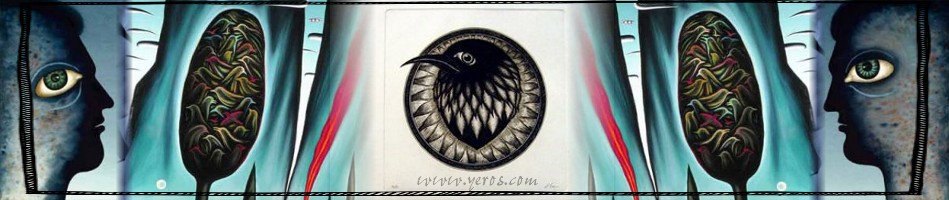

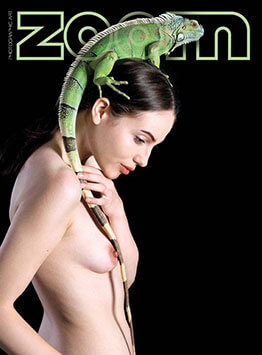

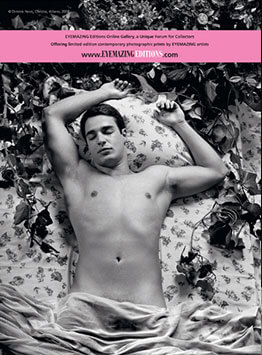

One might expect, perhaps, that the paintings would resemble the photographs, but this is not the case. At times they seem like the product of two quite separate artistic personalities. There are, of course, things that they share. The chief of these is their affiliation to Surrealism. A nude young woman will have a torso wreathed in ivy, and her skin will be adorned with snails. An equally nude young man, seated behind a table, will studiously ignore the pea-hen perched at one corner.

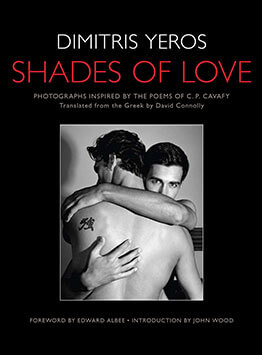

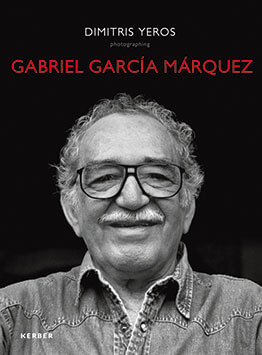

Not all the photographs are like this. Some are celebration of the athletic male body, with no additional accoutrements. Some are penetrating informal portraits of literary and artistic celebrities. These testify to the breadth and variety of Dimitris Yeros’s friendships. Where else but on his Internet web site would one find the American artist Jeff Koons cheek-by-jowl with the great Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez? A recent series, still in progress, consists of images that comment on the poems of Cavafy, often using contemporary celebrities as surrogates for the now-departed poet.

Whatever their subject-matter, the photographs have complete technical control, and an unerringly extroverted sense of style.

When one looks at Yeros’s paintings and at the prints related to them, the situation seems very different. The link to Surrealism is still there – in fact, it is even closer. But the paintings are introverted where the photographs are extroverted. They have nothing to do with the sensuality of the body, fascination with which plays such an important role in many of the photographs. The paintings are concise emblems – each is a summary of an emotional state. Certain basic images recur – birds, for instance, and fish – but these are reduced to their most basic, diagrammatic form. When human beings are portrayed, they too are diagrammatic. Yeros’s typical ‘running men’ remind us of the men in bowler hats that regularly appear in paintings by Magritte. They are never individuals, but cloned versions of a bourgeois everyman.

Why does this contrast exist? Photography, as an artistic medium, is dependent on the external world. That is to say, the photographer has to find something – some body, some place, some incident in the external world – that he wants to portray. Of course, he can to some extent create these incidents. The snails and the pea-hen, included in two of Yeros’s photographs that I have just described, did not arrive of their own accord. He had to imagine their presence, find them, and then use them for his own purposes. Paintings do not require this process of discovery and compilation – or only sometimes, not invariably. Yeros’s paintings are snapshots of his own psychological condition – but to make them he does not need a camera. He only has to look into himself, with an unblinking gaze. This cool consideration of the self is certainly something that Cavafy would have sympathized with, though he offered his own results in such a different form.