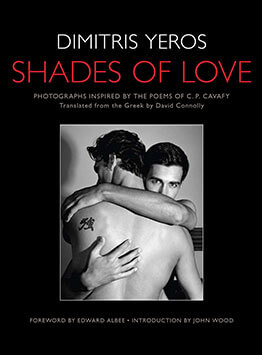

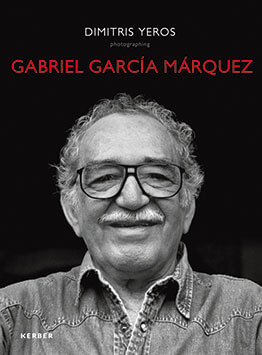

by Paul LaRosa essay from the edition of 21st , 2004

Chiseled Tableaus: The Nudes of Dimitris Yeros

In a moment of unadorned melody--a fragment of birdsong, a Chopin Prelude--the cords within us bend and turn. Time suspends, and from a single nuance, a world unfolds. The solitary nude, pure and unambiguous, is a similar melody, one keyed to beauty and simplicity, a rhythm in which we move in unison. In lowered eyes our desire is merged; from line and limb we quarry the substance of life and love. Each gesture of the body is a moment both intimate and vast, a summation of sense and the lineament of thought.

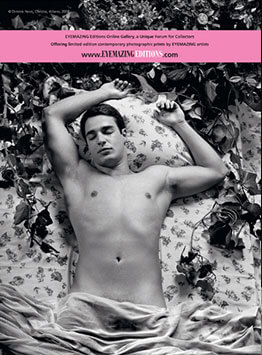

Dimitris Yeros captures such moments in lyrical photographs that celebrate the beauty of the male body. His nudes distill an unspoiled essence and vitality, discovering gestures and nuances in the body that are infinitely revealing and self-renewing. In their presence, time seems to melt away, and a world of wonder is disclosed, a world scaled both to intimacy and to universality, in which spirit and flesh harmonize. Staged to face us directly, Yeros' nudes are palpably real and teeming with presence--breathing, blinking, pulsing--but at the same time they glow like deities newly imagined. They awaken us to destinies of love and desire, to origins and intangible essences, and in their curves resides the intoxication of instinct. Lucent and visional, they seem brought from the sun, caught by stars, and bent by the moon.

Acclaimed as a painter and photographer, and widely exhibited at home in Greece and abroad, Yeros has also produced sculpture and poetry, and is one of the first video artists. All is concentrated in a pursuit of beauty nourished by an amazement for life, an adulation of youth, and a clear and abundant eroticism. Purity and immediacy define his work, and a fulsomeness that is achieved through clarity, simplicity, and play. Yeros' sensibility is ludic and intuitive, embracing the unexpected through gently surreal arrangements, peculiar combinations that imbue his art with originality and an inherent sense of joy--a joy akin to a child who suddenly runs simply because it is possible, for whom movement precedes purpose. Yeros' photos are governed by the same spirit of openness and spontaneity. They may be staged, but they also seem discovered in their own making. They preserve the ephemeral and entrust themselves to the moment, exuberantly.

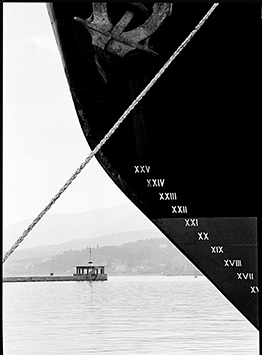

This is not to say that his work lacks depth or refinement. On the contrary, it is as contemplative and exquisitely layered as it is simple and celebratory, and it innovates a genre choked with solipsistic gestures, too often bereft of substance, feeling, or originality. A lustrous quality permeates Yeros' prints, with tonal contrasts that are richly suggestive, neither austere nor distancing. Symmetrical and precise, with direct and absolute perspectives, his images of nude males appear as chiseled tableaus, and yet their sculpture belies a natural rhythm, a nimbleness and flux. From darkened chambers that resemble both deep pools and the broad canvas of dreams, figures emerge and assert themselves, irradiant and reborn. Fingers uncurl and extend, clutching sides and grasping feet, quizzically exploring the contours of the body, as if each muscle and bone harbored its own hue, as if the body were a kind of mandala. In these postures Yeros crystallizes moments in which the body is a threshold to self-discovery.

On one hand his nudes, statuesque and ennobled, partake of a tradition of Classical sculpture. Rendered in elongated lines, they appear like marbled forms lit from within, kouroses gilded by fire, uneroded and quintessential. Often they rest on draped tables and pedestals, displayed like frescoes or altarpieces, elevated as icons and artful marvels. We recognize a Classical tradition at work, albeit one that is innovated and revivified. Surreal flourishes abound, maverick flights of the imagination that disrupt our expectations. A boy's torso is covered in snails. The elegant supine pose becomes an arching sprawl, unsure of conclusion. Twisting limbs and leaning postures imitate the symbols and forms of language--alphabets, zodiacs, arabesques. At times, the angled placement of the body seems to suggest the machinations of an unseen puppeteer at work in the background. But the figures are too sensuous to represent dolls, too alive and protean and with gestures too expansive to stand as symbols for the workings of fate. Rather, it is as if his models were released from the temples into the world of the flesh, in which they find themselves vexed by ardor and a newfound freedom, spellbound by a nascent awareness of the body. Their movements are orchestrated yet informal, compelled forth as tides by the cycles of the moon.

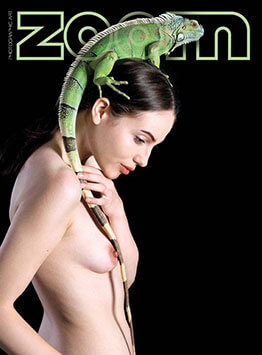

A melodious and organic quality keeps these photos natural and intuitive. The props which accompany his nudes seem chosen as Mediterranean icons of simplicity and bounty, resonances of life at its most elemental: apples and lavender, jugs for water, sheaths and wooden tables. Sometimes Yeros pairs his nudes with animals, establishing a kinship that underscores their earthiness and reaffirms our bond with the natural world. In other instances his figures seem animalistic themselves, poised to pounce, transfixed by rut. Issued forth from primal movements and the rudiments of life, Yeros' work is generative and embryonic. It is not exiled from nature, but resident at the very core. I liken it to a pearl brought forth from the depths of the ocean: unique, whole, sensuous and luminescent.

Nothing is decorative or superfluous in Yeros' photographs, and at the same time, nothing is overtly conceptual; the images are essentially associative and imaginatively layered. In one mesmerizing photo, a naked youth, wide-eyed and content, is covered in snails and garlanded with ivy. Painterly and serene, the image is an inspired reinterpretation of the still life banquet, a curious reworking of familiar signs of bounty. But Yeros transcends the rules of any formal game, harnessing an energy that propels the image into the realm of the visionary and the erotic. Like some mythic being, the boy appears newly sprung from the clay of the earth, a living embodiment of the creative force of nature. He emanates a sexuality that is steady and harmonious, a magnetism blended from his tensile limbs, his balanced posture, even from the wet snails that trail across his skin like a succession of kisses. Yeros speaks eloquently to the dynamism of nature, its richness and juvenation. He locates the fantastic within the real, the spirit within the flesh, and as in much of his work, they culminate in an eroticized image of a beautiful boy, an evocation of youth as the sensuous body of the world, fertile and enfolding. We see it again in his photograph of a beautiful young peasant, flaxen-haired and with lips gently parted, who sits naked on a cropping of rocks under a moon-bright sky, encircling a clay urn with delicate hands--a radiant image draped in a mood of expectancy and offering, far removed from any Orientalist vision of exotica. The boy's languorous gaze and the lush chiaroscuro recall the seductiveness of Caravaggio. The image is powerfully erotic, timeless, and peaceful, threaded by a dream of desire and eternal youth. Here is Antinous, the teenage lover of Hadrian, whom Fernando Pessoa immortalized in verse: young and golden-haired, and with "eyes half-diffidently bold"; a "flesh-lust raging for eternity," in whose presence "thou wouldst tremble and fall."

The charged eroticism of Yeros' work often rests in dualities that are skillfully balanced: stillness and motion, the hidden and the exposed, the visionary and the vernacular. A photograph of a boy standing naked, arms outstretched and shielding his body with an opaque curtain, strikes us by an understated yet pronounced complexity. The image is a potent, tactile embodiment of lust and temptation, and at the same time it bestows a sense of innocence and evanescence. Yeros' veil, fluid and impermanent--a counterpoint to the immotile stance and stare of the boy--brings light out of darkness, but it also returns us to a world of secrecy and untapped desire. In its folds seem to lie the currents of the boy's inner world--hope and longing, emotional life, love and sex. More mirror than barrier, and with a dreamy texture that summons contemplation, it harnesses our thoughts as well, a gateway to reflections on the quixotic nature of desire and the passing of time, and the irreconcilable exchange between what is attainable and what forbidden, in which all our lives dwell.

Look at his serpentine image of dark-eyed youth, a male Salome with arms raised and body stretched--a brooding, enthralling depiction of male. We recognize a sexuality that is all-encompassing, that translates the full range of human emotion and experience. It is at once calm and devouring, lyrical and raw, and it seizes on all the senses.

For Yeros, love, beauty and desire are celebrated as equal feasts, sustenances drawn from an essential world of plenty. They nourish his art and instill it with sentience and significance. Rapturous and alive, his nudes are keyed primarily to our senses: they stir and reverberate; we shiver, sigh, and tremble. But they also incarnate the fundamental rhythms of nature, like poems tracing paeans to the interconnectedness of life, its abundance and endless possibilities--as if anchored, in "delicious solitude," in the same pungent natural world of Marvell's "Garden." Their erotic presence fuses the earthly with the ethereal, sex with spirit and sublimity, and it speaks to a kind of perpetual wonder and veneration that is deeply and commensurately felt. It became all the more apparent when, as I sat writing this essay one February morning, I noticed a strange and beautiful confluence of events outside my window, a phenomenon I have rarely glimpsed: a dense curtain of descending snow, and the sun burning bright through shifting clouds, igniting the air. I stopped my work and stood outside, a captive witness to Nature's caprice--an occurrence unique and resplendent, both detailed and immense, still and dynamic, showing a world wending toward harmony. "Wedding of foxes" it is called in Japan. When the snow stopped I returned to my table, and once again looked at beautiful Greek nudes. Surely Dimitris Yeros would be inspired by such a sight, and would understand, who captures the same resplendent world, provokes the same sensations in his glorious photographs.